I have gotten several emails over the past several months asking about aircraft turbulence and how they can avoid or lessen their exposure.

As both a meteorologist and an individual who is not crazy about bumping around in the sky, I have had a lot of interest in the topic. And I talk about this issue in some depth in the senior weather prediction class.

So let me give you my take in this blog.

Meteorologically there are various origins of the turbulence motions that can make flying unpleasant.

The worst is turbulence associated with thunderstorms and cumulus convection.

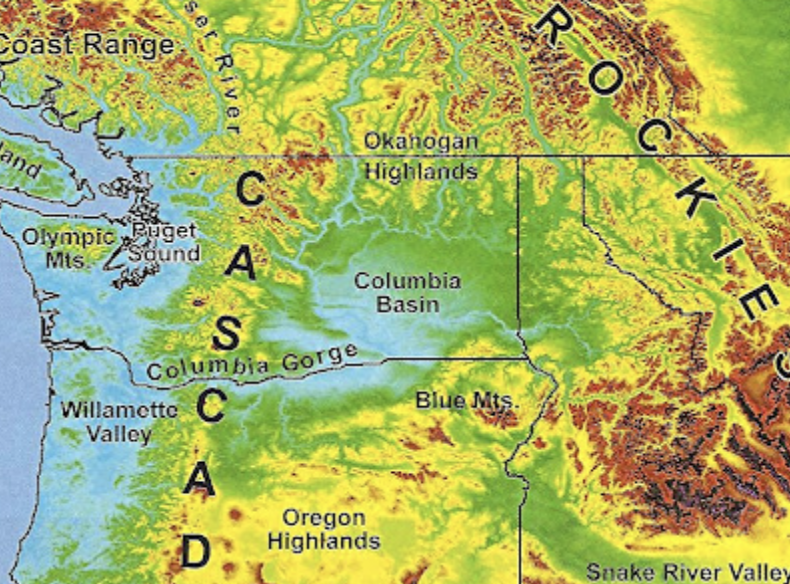

Turbulence can also be caused by strong, turbulence motions associated with mountains. This includes mountain-wave turbulence over and downstream of terrain.

Turbulence can be produced by large wind shear when wind speed or direction changes rapidly with height.

Turbulence can be associated with heating at the surface, which produces low-level convective mixing that is most apparent at landing or take-off.

And turbulence can be produced by strong winds interacting with surface features, like hills and buildings.... something called mechanical turbulence.

Where you sit on the plane makes a difference

Sitting over the wings in the middle of the aircraft near the center of gravity helps.

This makes sense because the center of gravity acts like a fulcrum for several types of motions that occur during turbulence, except for up and down vertical excursions.

Thunderstorms can produce very unpleasant turbulence and they generally increase in intensity during the afternoon hours.

Thus, during the summer when thunderstorms are more frequent flying early can really help.

I fly to Denver a lot, a location where thunderstorms develop over the Rockies during the late morning and then move out to the east over the airport in the afternoon. My plan is ALWAYS to arrive or leave there before 11 AM.

In general, when flying anywhere over the eastern two-thirds of the U.S. in summer, get in and out early, before the boomers start.

Wind shear turbulence and mountain-related turbulence are worse in winter when winds aloft are strongest.

Knowing What to Expect Helps

For me, understanding the situation before I take off helps. Knowing how long the turbulence will last helps.

It turns out that pilots report in flight about turbulence, in messages called pilot reports or PIREPS.

You can go to a government website and see the locations, levels, and intensities of turbulence (see below). Turbulence is divided into light (green), moderate (orange) or severe (red). Most turbulence is light. When you hit moderate it becomes unpleasant and the seat belt sign is always on. In severe, stuff can hit the ceiling.

It is always good to have your seatbelt on as a matter of course and ALWAYS use it for moderate and severe.

On that government website you can even view predictions of non-convective turbulence produced by software that relates weather model forecasts to the production of turbulence (see below). I find that it has quite useful skill, but not perfect.

Some private sector companies provide turbulence guidance as well, such as turbulenceforecast.com, and will even provide a custom turbulence forecast at a reasonable price. If you get internet on your flight, you can check on things as you fly.

Finally, if you are like me and enjoy a window seat, keep an eye out on the clouds ahead.

Substantial turbulence is often associated with KH-instability clouds that look like this:

Looks like waves breaking on the beach, and like such water waves, they are associated with turbulent motions.

On one flight, when the seat belt light was off, I saw such clouds ahead and advised the woman next to me to buckle her seat belt. She laughed at me.

We hit some substantial (moderate+) a few minutes later and her drink spilled. She kept the belt on the rest of the flight.😜

.png)

.gif)