European weather prediction models proved to be substantially superior to U.S weather prediction systems predicting the track of Hurricane Ian.

Weather radar image near the time of Ian's landfall on the

west coast of western Florida today.

This is an issue I have blogged about and written papers about in the past, with the most well-known past case being Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

And it reflects the decline of U.S. national weather prediction skill versus leading international centers--a situation that is a national embarrassment and must be fixed.

Let me show you the unfortunate details for Hurricane Ian.

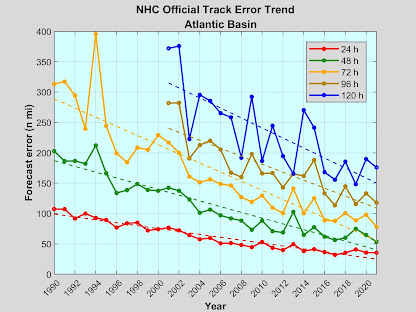

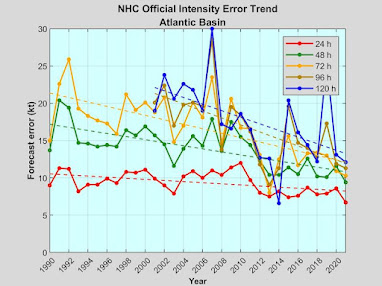

I will start with a graphic of forecast track error by Professor Brian Tang of the University of Albany (website here). This figure presents the track error (in km) for various forecast lead times.

The main US global model (the GFS) is shown by the dark red color (AVNO), while the leading weather prediction center in the world (the European Center) is shown by blue (ECMF). The high-resolution US hurricane models (HWRF and HMON) by purple and cyan, and the official forecast (with human input!) by the black line.

For the short-term forecasts (24 or 48 hr) everyone was on the same page.

But look at the extended forecasts (96 and 120 hr)! OMG. The European Center was the clear winner, with roughly HALF the track error of the US global model.

Furthermore, it is very concerning that the U.S. high-resolution hurricane models (HWRF and HMON) had even larger track errors.

High resolution doesn't do you much good if you get the storm in the wrong place!

Let me show you the problem spatially by presenting the tracks of the U.S. and European ensembles of many forecasts, with each forecast providing a track of the storm.

Below are the forecasts starting at 0000 UTC 25 September (Saturday at 5 PM PDT), with the black lines showing you the mean track of all the forecasts). (imagery courtesy of weathernerds.org)

The European Center forecasts were very good, suggesting landfall on the central and southern western coast of Florida. South of Tampa. Quite close to the actual landfalling position (as shown by the radar image above)

In contrast, the US GFS ensemble was displaced much more to the west (which was wrong). Much more spread (uncertainty). The U.S. forecasts were MUCH more threatening to Tampa, since a storm making landfall north of Tampa could push water into the bay.

As a result of the problematic U.S. forecasts, the media went nuts talking about a catastrophic storm surge in Tampa, with calls to evacuate hundreds of thousands of people. And people down the coast were not warned of a serious threat.

I wish this was an isolated case, but it is not.

U.S. global weather prediction is not as good as some major international centers, and the cost to the American people is enormous (can you imagine the costs of all the evacuations in Tampa, for example).

The U.S. has the largest and best weather research community in the world. We spend more on weather prediction than anyone else. Yet, our forecasts are not as good as others. And a shadow of what we are capable of.

I have written a new paper describing the origins of the problem. It is a problem of organization, of duplication of efforts, of no one group or individual being responsible, and a lack of a coherent system for improving our weather models.

And it will take the active intervention of Congress to fix it.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.gif)

.gif)