During late 1944 and early 1945 over 9,000 of these terror balloons, known as Fu-Go, were launched by Japan, with the goal of starting massive forest fires over the western U.S.. Only about 300 were documented to reach western North America and they proved to be ineffective weapons. Regrettably, six people lost their lives when they happened upon and explored an unexploded Fu-Go.

There are several books about these fire balloons, one I just finished reading: Fu-go: The Curious History of Japan's Balloon Bomb Attack on America by Ross Coen. Interestingly, this story begins with Japanese meteorological studies during the 1920s.

During the 1920s, a Japanese meteorologist, Wasaburo Oishi, began probing atmospheric structure from a site near Mount Fuji by launching a series of weather balloons called pibals (pilot balloons). By tracking these balloons with a small telescope and doing some simple trigonometry, it is possible to determine the wind speed variation with height (assuming the balloons move with the surrounding air).

Wasaburo Oishi, often considered the discoverer of the jet stream,

Wasaburo quickly found something of great interest during 1923 and 1924: during the winter the winds often increase with height, with winds of great speed located 25,000 to 35,000 feet above sea level, something that later became known as the jet stream (see a figure from his famous 1926 paper).

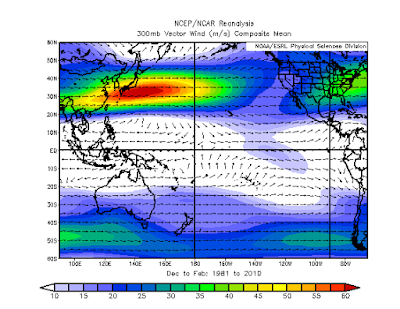

His 1926 paper did not get a lot of attention because it was written in Esperanto, but today many people give him credit as the discoverer of the jet stream, the current of westerly strong winds (reaching 150-250 mph at placea) in the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere. The Pacific jet stream is known as the strongest in the Northern Hemisphere and is often located over Japan. To illustrate, here is the average upper tropospheric winds (300 hPa, around 30,000 ft) for Dec-Feb 1981-2010. The winds are in meters per second. Roughly double for knots or mph. South/central Japan is jet stream heaven; Ooishi had a big advantage!

During the 1930s, German meteorologists documented the jet stream over Europe (much weaker) and during WWII the jet stream had a huge impact on aircraft operations, sometimes causing westbound aircraft to lose virtually all their ground speed.

As World War II went increasingly against the Japanese, their military decided to try a last-ditch effort to terrorize the U.S. and to force the Americans to divert their resources to fighting fires: the Fu-Go fire balloons. The work of Ooishi and other Japanese meteorologists delineated the existence of the jet stream and the military believed that weaponized balloons could reach the U.S. in 3-5 days.

The fire-balloons were made of paper, 30 feet in diameter, and had an ingenious ballast mechanism (with dropping sand bags!) to keep the balloons at altitude. At the end of its flight, each balloon could drop a collection of incendiary bombs (see image)

Sand bags and fires bombs hand from the lower portion of the Fu-Go fire balloons.

Although most of the balloons crashed in the Pacific, hundreds made it to Alaska and the western U.S. (see map), some getting as far as Iowa. Quite a few landed in the Pacific Northwest, but none were effective in starting fires.

Landing sites of Fu-Go balloons

The Japanese had meteorology against them: the jet stream is strong during winter (November through March) when the western U.S. is not vulnerable to fires. During the summer, when our forests and rangeland are dry, the jet stream is too weak to serve as reliable cross-Pacific transportation.

As I have noted in previous blogs, although fire balloons are not coming from Asia anymore, smoke, dust, and other pollutants are frequent, unwelcome, hitchhikers on the strong Pacific jet stream winds.

I believe there is a historical marker near Klamath Falls, Oregon that states that several members of a Southern Oregon family were killed and injured by one of these balloons. If memory serves, it happened when they came across an unexploded one and investigated it.

ReplyDeleteHere is more information on the balloon bomb.

ReplyDeletehttp://www.oregonlive.com/history/2015/05/past_tense_oregon_70_years_ago.html

Radiolab did a program on it, which has more details on the deaths in Oregon, and more photos:

ReplyDeletehttp://www.radiolab.org/story/pictures-fu-go/

And the podcasts:

http://www.radiolab.org/story/fu-go/

Many of us with roots in the Northwest knew about the balloons. I remember my dad mentioning them many times.

He may have known more than others since after graduating from high school in 1944, he joined the Army and was assigned as an MP for the Manhattan Project in Hanford. Obviously they were on the lookout for those balloons.

There is a considerably less comical side to this: Japan's "Unit 731" germ warfare program, a bit of ugliness mostly lost in the sands of history.

ReplyDeleteFor centuries -- long before the industrial era -- Japan was a leader in ceramics. They still are today. After they took Manchuria and then China, the Japanese bred plague-carrying fleas. They were put into ceramic containers while alive, and floated on balloons over Chinese rural areas. They landed, broke apart, and the fleas infected peasants with the plague.

Then the Japanese soldiers assigned to "Unit 731" went into those areas and, among other things, performed dissections of sick people, while they were alive, without anaesthesia, to monitor the progress and effect of the disease. At least 500,000 Chinese died as a result, and to this day there are periodic outbreaks of plague in China that are traceable to this activity.

The Japanese had planned to do the same to us, but the failure of the bombs caused them to change the plan. Instead, they planned (and might have built one or two, I forget) gigantic submarines capable of carrying small airplanes. Their aircraft carriers had been destroyed; the idea was that the U.S. would never even look for subs in the Pacific.

The subs would carry the planes, but instead of dropping explosives they would drop the insect-carrying containers over West Coast cities. Separately, the Japanese had two independent research units -- one in Tokyo and another in present-day North Korea, which the Japanese had invaded and occupied in 1915 and thereafter -- working on an atomic bomb.

The Tokyo atomic effort was destroyed by the famous Doolittle raids that burned most of that city to the ground. The Korean effort is thought to have succeeded in exploding a test bomb. But it was too late: Auguist 12, 1945. When the U.S. and the Soviets divided Korea after the Japanese surrender, each side had separate reasons to keep the nuclear program under wraps; the truth came out in the '00s (or maybe the late 1990s), to hardly any notice or acclaim. I saw the interview with one of the scientists who directed it.

The plague-bomb effort depended on the submarines, but American bombing so thoroughly decimated Japan's industry that they couldn't make the plan come together. So, as quixotic and almost comical as those balloon bombs appear today, this was not a casual effort. What I don't know is why the Japanese didn't just start with the plague insects from the beginning.

Additionally, much of the Unit 731 history was buried after the war, when the U.S. military decided the data would be useful. The level of scrutiny and published detail about Japan's war crimes, of which Unit 731 was by far the worst, was far less than what was published about German war crimes.