Several of you have asked me about viewing the presentations at the recent Northwest Weather Workshop. Well, you can!

The meeting was recorded and if you want to view any of the sessions, feel

free to check out the zoom links below.

The agenda is found below and here:

https://a.atmos.washington.edu/pnww/index2023.php?page=agenda

Friday, May 12

https://washington.zoom.us/rec/share/GGu7tIz75jrev8WV0A2b88xxBr8DZoVw03meJzhsnFyb45Dd8AkNP7-Kq6Aop5xq.v63DWYCddGskqgFl?startTime=1683919622000

Saturday, May 13

https://washington.zoom.us/rec/share/LVLwZWkxHGJz3kZXYYjxLWtTbD_XrjPSJD_rqILiBDqnnAF_XEw4RJ37Y92N04al.DDK6krV5QUZSJ5cO?startTime=1683990927000

Northwest Weather Workshop 2023

Sponsored by the NOAA/NWS, the University of Washington, and the Seattle and Portland Chapters of the American Meteorological Society. Online.

Friday, May 12, 2023

1:00-1:10 PM Welcome and Meeting Details

Special Presentation

Session 1: Heavy precipitation and atmospheric rivers over the West Coast

1:10-1:30 Summary of west coast atmospheric rivers of 2022/23F. Martin Ralph Director, Center

for Western Weather and Water Extremes (CW3E) - UC San Diego

1:30-1:45 The Great West Coast floods of 1861-62 compared to last winter – what’s the

difference? Larry Schick Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes (CW3E)

1:45-2:00 Usage of Satellite data to detect heavy precipitation and flooding events in British

Columbia and California. William Straka III, CIMSS/NOAA/LEO

2:00-2:15 PNW Water Year Impacts Assessments. Karin Bumbaco and Crystal Raymond,

Office of the Washington State Climatologist, CICOES, University of Washington

2:15-2:30 Development of an Impact Based Storm Rating Scale for Decision Making in a Warming World: Demonstration using Major Extratropical Cyclone-Atmospheric River Storms between 2020-2023. Melinda M Brugman, Alex Cannon and the ARkSuperStorm team

2:30-2:45 Coastal Flooding in Western Washington and the December 2022 event.

Kirby Cook, Science and Operations Officer

2:45-3:00 What we have learned from the Olympic Mountains Experiment (OLYMPEX) about precipitation processes in complex terrain. Lynn McMurdie, University of Washington

3:00-3:30 PM Refreshment Break

Session 2: Snow and Avalanche Forecasting

3:30-3:45 The Meteorology of Avalanche Forecasting. Dallas Glass

Deputy Director- Avalanche Forecaster, Northwest Avalanche Center

3:45-4:00 Impact-Based Decision Support Service Ahead of Record-Breaking Pacific Northwest Cascade Snowfall, Charlotte Dewey, National Weather Service, Spokane, Washington

4:00-4:15 The Surprise Portland Snowfall of Feb 22...What did Satellite Products and

Analysis Show. Sheldon Kusselson, Cooperative Institute for Research of the Atmosphere (CIRA)/Colorado State University

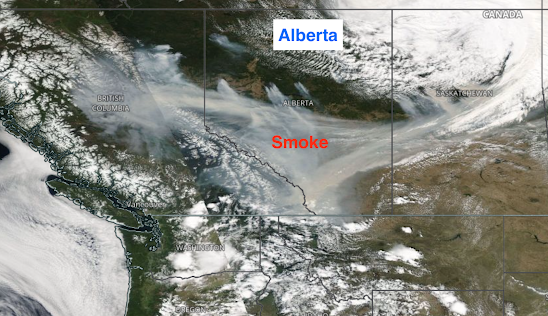

Session 3: Wildfire Forecasting and Smoke

4:15-4:30 Tracking wildfire smoke with lidar-ceilometers. Phil Swartzendruber, Puget Sound Clean Air Agency

4:30-4:45 Update on our Geostationary GOES-R Capabilities for Tracking Fires and Smoke. Mike Stavish, Science and Operations Officer, WFO Medford

4:45-5:00 Research Support for Crisis Strategy Prescribed Burns. Marlin Martine, Brian Potter, Andy Chiodi, Joel Dubowy, Aaron Rowe, Vaughn Cork, Steve Bodnar, Ernesto Alvarado Sim Larkin, Susan O'Neill, Tony Bova

6:00-9:00 Workshop Banquet at Ivar’s Salmon House, Seattle

Banquet Talk: Mathew Dehr, Meteorologist, DNR

Washington's Outlier Wildfire Seasons and Events: A climate and weather perspective.

6:00-7:00 PM Icebreaker – no host bar

7:00-8:00 Buffet Dinner

7:45-8:30 Presentation

Saturday, May 13, 2023

9:00-9:10AM Welcome

Special Presentation

9:10-9:25 Future Directions of the American Meteorological Society. Dr. Brad Colman, President, American Meteorological Society

Session 4: Northwest Climate and Weather

9:25-9:40 Extreme Weather Events in WA State: Variations and Trends. Nick Bond and Karin

Bumbaco. Office of the Washington State Climatologist, CICOES, University of Washington

9:40- 9:55 Observed and simulated characteristics of down-valley flow within stratiform

precipitation over the Olympic Peninsula. Robert Conrick, Joe Boomgard-Zagrodnik (presenter), Lynn McMurdie

9:55-10:10 Why was the June 2021 Heatwave so Severe? Cliff Mass, David Ovens, Robert

Conrick, and John Christy.

10:10-10:25 Future Climate Simulations for the Salish Sea Using Dynamically Downscaled

Atmospheric Projections/ Eva Gnegy. UBC - Dept. of Atmos Science1; Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO)2

10:25-10:55 Refreshment Break

10:55-11:10 Regional Climate Modeling. Eric Salathe, UW Bothell

11:10-11:25 A recap of the Feb 22, 2023 Portland Snowstorm. Tyler Kranz, Lead Meteorologist, NWS Portland

Session 5: Regional weather prediction and communication

11:25-11:45 The UW Dawgcast. Shannon O'Donnell, KOMO TV and UW

11:45-12:00 Update on the Northwest WRF Modeling System. David Ovens and Cliff Mass

12:00-1:00 PM Lunch

1:00-1:15 Managing a Weather Social Media Site, Justin Shaw, SeattleWeatherBlog

1:15- 1:30 National Weather Service Social Media Outreach. Logan Johnson, MIC, and Jake DeFlitch, NWS Seattle

1:30-1:45 Weather Support at Alaska Airlines. Michael Snyder, Alaska Airlines

1:45-2:00 The High-Amplitude Gravity/Wind Event of May 2, 2013. Anthony Edwards,

Atmospheric Sciences, University of Washington

2:00-2:15 Rotating Convection Near Terrain. Steve Businger and Terrence J. Corrigan Jr., University of Hawaii.

2:15-2:30 PM. Video Weather Highlights, 2022-2023. Greg Johnson, Skunk Bay Weather