A major hurricane is hitting the Gulf at just the wrong place for New Orleans and environs.

Hurricane Ida, a category four hurricane with winds gusting to 150 mph is now making landfall.

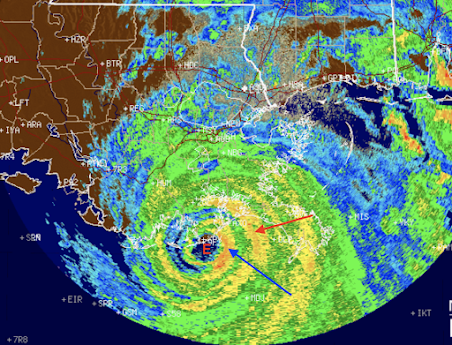

The latest weather radar image (showing intensity of precipitation) clearly shows the eye of the storm (letter E!), just making landfall on the Lousiana coast (below).

Ida has a compact eye, with the eyewall apparent in the precipitation band indicated by the blue arrow. A secondary eyewall appears to be forming (red arrow), which is temporarily weakening the storm (it might have become a category five storm if the second eyewall did not start to form.The infrared satellite picture (which is essentially providing the temperature of the clouds and surface) is impressive-- the eye is small, but well defined, with high clouds (red colors) surrounding it.

The small size of the eye is a very good thing because the strongest winds are limited to the area in the eyewall of the storm. Here are the latest wind reports (10AM), with the gusts shown in red (click on image to expand). Gusts to 89 mph. Note the strong easterly (from the east) winds moving towards Lake Pontchartrain and New Orleans. Not good...pushes water onto land in the form of a storm surge.

Maximum winds gusts so far (see below) have ranged as high as 128 mph

The storm will weaken as it moves over land, but extremely heavy precipitation can be expected, with totals reaching 15-20 inches in southern Lousiana and large rainfall totals extending into the Northeast U.S. (see NOAA/NWS forecast below)

Predictability of the Storm

The forecast of Hurricane Ida is classic: extremely good forecasts for the storm track many days out, but the forecast of the storm intensity (central pressure and maximum winds) underplayed the storm.

The forecast tracks of major U.S. and Canadian models on Friday morning were quite good, but were slightly too much to the west. (black line shows the observed track).

By yesterday morning, the track forecast was excellent.

But what about the intensity forecast on Friday? One measure of intensity is the central pressure of the storm (the lower the pressure, the more intense). The latest observations indicate the low center is down to 930 hPa (hPa is a unit of pressure). Here are the forecasts from yesterday morning (black line indicates the observed). None of the forecasts got the storm deep enough. As a result, their winds forecasts have been too low.

As shown by this graphic by Dr. Brian Tang, University of Albany, the winds were about 25 knots too slow for the 47 hr forecast and about 50 knots too slow for the 72 h forecast.

Why are our models frequently unable to get the intensification right? One reason is the lack of resolution. To simulate such storms one needs to simulate the hurricanes with model grid spacing of approximately one kilometer or better, but the National Weather Service lacks the computer resources to do so.

Then there are deficiencies in model physics, such as how sea spray humidifies the air above the breaking waves. Or how cooler water mixes vertically in the upper ocean surface.

And then this the need for model data to describe hurricane structure offshore.

An apparently significant issue for Hurricane Ida was a patch of deep warm water over the Gulf of Mexico, directly on the track of the storm (see below). Such warm water greatly helps a storm to intensify.

Finally, one thing to keep in mind: our ability to predict the tracks, and to a less extent the intensity of hurricanes, is a potent tool for reducing damage and casualties from tropical storms and hurricanes.

It is why tropical storm deaths are far fewer today than 50-100 years ago, even with many more people on the planet.