The media frequently talks about trends in precipitation, sometimes describing increasing drought and sometimes suggesting precipitation is increasing.

Of interest, both increasing drought and increasing precipitation are often "explained" by global warming.

In any case, instead of speculating about precipitation trends, let's check out what the real world is telling us.

That is the topic of this blog.

Let's start with Seattle-Tacoma Airport, Washington, whose record goes back to the mid-1940s. Below is a plot of its annual precipitation. There is little overall trend. A bit wetter during the early and later periods perhaps, with an average of around 39 inches. There is no real trend in magnitude of the extremely wet years.

Pretty much the same thing for the wet season (Oct 1- 30 March) when the bulk of Seattle's annual precipitation falls. The cool-season average is about 30 inches.

In contrast, there has been a modest drying during the summer (June through August), with warm-season totals dropping from roughly 3.8 to 2.9 inches. Much of this trend is due to fewer extremely wet summers.

Olympia is similar (I checked).

What about Eastern Washington?

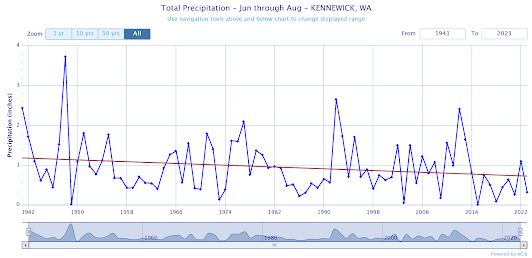

Let's check out Kennewick in the Tri-Cities, right in the middle of the Columbia Basin.

For the annual precipitation, very little trend (with an average of about 7.5 inches per year). No real trend in extremes.

Winter precipitation at Kennewick has very little trend.

Summers in Kennewick have become a bit drier, dropping from roughly 1.2 inches to about 0.75 inches

It is also possible to plot the average precipitation over the entire State of Washington, using the NOAA/NWS climate division data. Using this dataset the annual average precipitation is shown below, starting in 1950. No significant trend.

In summary, there is a robust message in all this, one confirmed by other stations I have not shown: during the past 70 years or so, total annual precipitation in our region has hardly changed. Winters have hardly changed. And summers have gotten slightly drier...but summers don't contribute much to the annual totals since they are typically quite dry.

So if annual and seasonal values have changed little during the past half-century or so, what about short-term extremes, such as those produced by atmospheric rivers?

Let's examine that using daily precipitation data. I found the top 30 two-day precipitation events at SeaTac Airport and then removed duplicate events (adjacent days sharing the same precipitation). That left 21 events. Below is a plot of these events over time (from 1951 to this year). The highest values ranged from roughly 3.5 inches to 5.25 inches over two days.

There is no evidence for an upward (or downward) trend in the heaviest precipitation events.

So if the heaviest precipitation events are not getting more intense, are they getting more frequent?

To answer that question, here is a plot of the frequency of the heavy precipitation events at SeaTac over time. Heavy events were particularly frequent from the mid-1990s to around 2011, and then lessened in frequency, followed by several events during the past two years.

Looking over the 70-year period, there has been an increase in frequency during the later half, but there is a lot of shorter-period variability. I published a paper on this issue about a decade ago with similar findings.

Could global warming be contributing to this increase in frequency but not in intensity? It is possible. I will talk about this issue more in a future blog.

Finally, with the recent rains, the Seattle water supply situation is back to normal. Reservoir storage is at average (see below)

And so is the snowpack above the reservoirs.

So if nature hadn't changed much and the perception had changed, then the logical reasoning would be that people had changed.

ReplyDeleteCan we get some deeper insight into the stats, Cliff? It seems like losing nearly an inch of rain over the summer on the west side is non-trivial. What is the r2 of that regression (or r if you were just running correlations)?

ReplyDeleteLoosing a modest amount of rain during West side summers may sound trivial, but I would expect it to increase the number of wildfires here. I think that that is what Hilary Franz has been concerned about. I have been hoping that AGW would tend to even out the yearly precipitation profile, but that does not seem to be happening. It might even make it more lopsided, if it comes to resemble the climate of, say, Eugene, OR.

ReplyDeleteIt seems that you are assuming the effects of global warming generally are linear...so that trends over the last 50 years are predictive of the next...what if they are non-linear, and we passed a threshold, say a few years ago.

ReplyDeleteI am making no assumptions of linearity...just showing you the actual numbers. And no suggestion of passing any threshold.

DeleteIt's only a response to media claims of what allegedly has already happened.

DeleteIf you want insight into what might happen in the future, including some discussion of non-linear responses, see the IPCC Physical Science Basis report, or look up some of the more locally focused work done by University of Washington.

The short summary is the long term effect of climate change is not expected to be linear. Overall, the Pacific NW is expected to get slightly more precipitation on an annual basis, but less of it in the summer, and more of it as rain vs. snow. And this effect will increase over time through the end of their primary forecast period (late this century).

One of the limitations is some of the effects are difficult to predict. If I remember right, the IPCC assigns medium confidence to the prediction of increasing storm intensity, versus medium-high confidence in the precipitation trends, but feel free to double-check my memory.

how about rain on snow events? Trends in freezing levels during these events? East of the cascades, even in the past decade, it seems like every storm we have tails out with a pretty sizable freezing rain event. Makes shoveling a nightmare.

ReplyDeleteOne thing I've heard asserted is that in addition to less rain in the summer, spring (May in particular) is less "cloudy" and thus there is more solar radiation hitting the ground and thus more evapotransportation and glacier/snow melt. Is there any truth to that claim?

ReplyDeleteHi Cliff - I would be interested in whether the frequency of large rain on snow events that occur during the November - December time period have increased in recent years. Thanks.

ReplyDeleteBut Cliff, in your blog of September 21, 2021, you clearly suggest that there is little change in our summer dryness over the past several decades. Would you like to clarify? My general impression is that yesterday's blog is more on target: My general impression is that summers HAVE gotten drier. Perhaps the measurements were made in a different location?

ReplyDeleteThe numbers suggest modest drying, but summers here are very dry anyway. Modest drying over the past 40 years...and about the same as 90 years ago.

DeleteHave you evaluated AI assisted forecasting? See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NItfn_8LUik for Atmos assist forecast for SpaceX.

ReplyDeleteVery helpful. Thanks Professor.

ReplyDeleteAnother factor is the relocation of temperature monitor stations during the past five decades - https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-11-800.pdf

ReplyDeleteWhile NOAA has closed many of these outdated and discredited stations over the past few years, they now claim that using satellite data is the most accurate measurement going forward, but also claim that they've adjusted the previous inaccurate readings accordingly. They're relying on the public's trust in these new statistics, but the public is wisely skeptical at this point.

The numbers and charts show that weather is variable. On the other hand, I live east of the Cascade Crest, a little north of Ellensburg.

ReplyDeleteLocally, there is a transition area between two biological communities, an ecotone where two communities meet and integrate. West is Ponderosa Pine and east is sagebrush-steppe.

Insofar as I know, not much has changed since about 8,200 ybp – the start of the Northgrippian age. The local situation may go back to the end of the Younger Dryas – about 11,700 ybp.

Confirming the above would involve more investigation than I am interested in doing. Sediment core {pollen & charcoal} and related work is available.

You know Clff, I actually do see a trend in your first two graphs on precipitation when you say there is not a trend. You are definitely using data trending since 1950. Start your graph at 1990. Anybody can say when the trend will start. I took statistics. I know that data can be manipulated. Most people do not remember what the weather was like back in the 1950's. I bet more people can remember the weather over the shorter period of time since the 1990s....and I believe more people can remember the weather since the 2000's too--hence the reason for "trends in precipitation". What is the definition of the media using the word "trend" and you using the word "trend"?

ReplyDeleteThe MSM uses the term "trends" only as a subjective and biased reason for their own narrative - and that narrative is that the world is on fire and we must spend trillions of tax dollars on dubious schemes in order to lower the overall temps less than one degree, at best. Actual science and data be damned.

DeleteThank you Cliff, I found this is very helpful. A few months ago, in response to media reports of long term drought in the area, I did an analysis of trends in total precipitation and summer precipitation using data from the airport in Victoria, British Columbia. The period of record (1941 to present) is very close to that of Sea Tac, and as you post shows, the results where consistent. The Victoria Airport data shows a very slight increase in annual precipitation since 1941, and a decrease in summer precipitation. The summer decrease was mainly due to the string of relatively dry summers since 2010. However, as far as long-term drought goes, the Victoria data does not support that. In fact, the driest period on record at Victoria airport was 1941 to 1943 where each year had annual precipitation below 70% of the long term average (1941 - 598.2 mm, 1942 - 557.3 mm, 1943 - 597.0 mm).

ReplyDeleteBLI has a 75-year period of record.

ReplyDeleteIt reported its 9th rainiest January on record during 2020, its 6th rainiest February on record during 2016, its 3rd rainiest March on record during 2017, its 7th rainiest April on record during 2019, its 7th rainiest June on record during 2022, it's rainiest September on record during 2019, its 3rd rainiest October on record during 2016, its rainiest November on record during 2021 and its 9th rainiest December on record during 2020.

9 out of 12 months have had top-10 rainiests and 4 out of 12 have had top-3 rainiests since 2016.

At the same time, only 2020 and 2021 feature in the top-10 rainiest calendar years on record. This location has certainly been receiving anomalously large amounts of monthly precipitation primarily during recent wet seasons.

Also, at the same time, it has been receiving anomalously small amounts of monthly precipitation during recent years. For example, the 4th and 5th driest Januaries on record occurred during 2023 and 2017. The 5th driest February on record occurred during 2022. The 3rd and 7th driest Marches occurred during 2019 and 2021. The 4th, 5th, 7th and 9th driest Aprils occurred during 2021, 2015, 2022 and 2020. The driest May on record occurred during 2018 and the 6th and 10th driest Mays occurred during 2015 and 2023. The 2nd driest June on record occurred during 2015. The driest July on record occurred during 2021. The 5th driest August on record occurred during 2017. The driest September on record occurred during 2022. The 6th driest November on record occurred during 2019.

10 out of 12 months have had top-10 driests and 5 out of 12 months have had top-3 driests since 2015.

Overall, the trend is toward increasing precipitation extremes, both wet and dry, primarily during the wet season and increasingly rainless dry seasons. However, wet extremes seem to be predominant overall as, prior to 2023, which will end up as one of the driest calendar years on record, there have been far more wetter than normal years rather than drier than normal years in the recent past. Given that summers are becoming drier, but calendar years wetter, it's clear that wet season precipitation is on the increase in general at this location.

No statistics with which to obfuscate. Just the actual data.