Help Determine Local Impacts of Climate Change

Society needs to know the regional impacts of climate change and a group at the UW is trying to provide this information with state-of-the-art high resolution climate modeling. With Federal funding collapsing, we are experimenting with a community funding approach. If you want more information or are interested in helping, please go here. The full link is: https://uw.useed.net/projects/822/home

_______________

The complaints have been non-stop, with even Northwest natives mumbling about one of the most persistently wet, cool, cloudy winters they can remember.

But tomorrow (Friday) will be better, with a transient ridge of high pressure over us, bringing dry conditions and temperatures rising in the upper 50s F.

Here is the surface air temperature forecast for 5 PM Friday from the high-resolution UW WRF model. The dark orange (over Seattle) indicates 56-60F, with 60s in eastern WA and parts of southwest Washington. I am looking for my sunglasses tonight.

But a single beautiful day does not make up for a challenging winter. Before I describe it, did you you know that SmartAsset real estate site has ranked Seattle as having the most depressing winters of any major city in the lower-48 states? This is based on the percentage of a sunshine rate and average solar radiation (see below). Only far north Anchorage is worse for the U.S. as a whole.

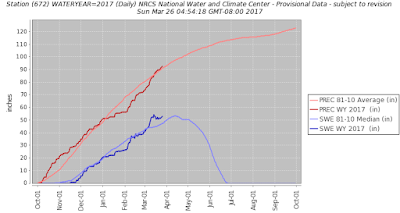

So I guess we start with low expectations. But this winter takes it one step further. Here is the number of days during the past six months with at least a trace of rain. 115-145 out of 180 in western Washington/Oregon were wet.

But the real depressing aspect of this winter is the continuation of the clouds and rain into late February and March, when major improvement is normally observed. Here are the number of days during the past 60 days with some rain. OMG... large swaths have had 50-55 days of rain out of 60 days (83-92%). This is way more than normal (typically in March in Seattle 55% days have some rain). MUCH worse than typical.

One of the faculty in my department, Dale Durran, has a solar array on his house. This March had far less power output than any of the five years the system was in place.

All the moisture and clouds has resulted in very wet soils, something shown by the NASA GRACE instrument that can measure soil moisture from space (below). Blue is highly saturated. My backyard is a mud pit now.

Our future? Some showers on Saturday, mostly dry on Sunday, warming into Tuesday. But the moisture returns, with the Climate Prediction Center's 6-10 day precipitation forecast covering our areas with the wet green colors. Sorry.