We have had a dry spring and summer and people are concerned. Completely understandable.

And people's discomfort and fears have been unnecessarily worsened by the incessant drumbeat in the media and some politicians that Northwest summers are been getting drier. And they are not shy about suggesting the cause: climate change or what was previously known as human-caused global warming.

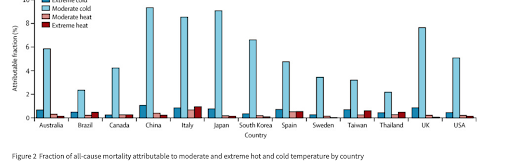

But is this really true? Do observations REALLY show that our region is getting progressively drier over the past decades and century?

The facts are clear: there is no long-term trend towards drier summers in the Northwest. And the effects of climate change (global warming) will be very small, with some locations receiving more summer precipitation. But as in real life, there are details and nuances that are generally not provided in the media.....let me provide them to you here.

Fact 1: The Pacific Northwest is climatologically one of the driest locations in the U.S. during summer.

Few places in the U.S. get less precipitation during the warm season than the Northwest, with our midsummer "drought" evident in the plot below. Eastern Washington also has its precipitation minimum during the summer.

Seattle Precipitation Climatology

As explained in my recent podcast (see below), the origin of the dry conditions is clear: during summer, the storm-bearing jet stream moves north of us, and the cool Pacific and an east Pacific high-pressure area lessen our chances of getting thunderstorms. Weeks or more without rain is not unusual in our region. It is why native plants are adapted to summer droughts and our eastside forests DEPEND on wildfire to remain healthy.

Fact 2: There Is Little Long-Term Trend in Summer Precipitation over the Northwest

Let's start with Seattle.

Recently, the Seattle Times did a story on how Seattle was experiencing the driest summer on record. Strangely, they published this story before the end of the summer and when a heavy rain event was in the forecast. Like doing a story on a low-hitting baseball game in the sixth inning with known sluggers soon at-bat.

The truth is that this summer (20 June 20-21 September) was the 24th driest summer in Seattle, considering observations going back to 1894. Not so impressive.

Let me show you a plot of Seattle's summer precipitation prepared by Dr. Joe Zagrodnik, a recent graduate of my department and currently a scientist at WSU. The light blue bars show the summer total precipitation each year. The black line shows an average (or smoothing) of annual summer precipitation.

You will note a few things. There are a lot of ups and down... or what is called interannual variability. This is not unexpected during a dry summer when a chance shower can make a big difference.

There is little long-term trend in Seattle's summer precipitation... the last 30 years is about the same as the early 20th century.

You will also note some long-term ups and downs: wetter in the 70s, drier around 1990, wetter in the early 2000s, a bit dier recently.

What about extreme dry years in Seattle? Is there a tendency to have more extreme dry years recently as claimed by some? To answer this question, below is a plot showing the distribution over time of the top ten driest years in Seattle.

Wow... most of the extremely dry years were early in the 20th century and there is clearly no upward trend in extreme dry summers recently. In fact, we seem to be having LESS extremely dry summers in Seattle.

What about the rest of Washington State?

Let's look at the NOAA/NWS climate division data, which unfortunately is only available on a monthly basis (below). This plot shows the July through September precipitation from 1900 through 2020 (blue line), plus a running average/smoother (red dots) to take out some of the variability.

Lots of ups and downs, but with little long-term trend. Some periods of high and lower precipitation as in Seattle. Perhaps slightly drier in the end.

Where did the years of driest summer conditions distribute over time for Washington State? Here is a plot of the 20 driest years for the state. The early part of the 20th century was dry, but there are few Northwest residents old enough to remember that period. Clearly, no long-period trend towards more extreme dry conditions.

Climate Change and Northwest Summer Precipitation

The implications of global warming on Northwest weather/climate is an area in which I am actively working on, under support from a variety of sources (such as Amazon's Catalyst program and the National Science Foundation). We (including Professor Salathe of UW Bothell, and UW scientists Rick Steed and Jeff Baars) are running state-of-science high-resolution simulations of the impacts of increasing greenhouse gases on our region.

Let me show you some regional climate forecasts using an unrealistically large increase of CO2 over this century (called RCP 8.5, often termed the business as usual scenario). So the actual changes should be less than this.

Here is the difference between the late 20th century and the middle of this century in terms of June-July-August precipitation. Small drying in the west and little change over eastern Washington. Eastern Oregon gets wetter.

Again, keep in mind that this forecast is using a very aggressive change in CO2-undoubtedly too much.

What does the model forecast for Seattle?

We ran an ensemble of many climate simulations starting in 1970, which are shown by the colored lines. The average of all these forecasts is shown by the green line and observations are indicated by black dots (the y-axis shows inches of precipitation). Not much change...just a very slight decline over time.

I could show you a dozen more of such predictions, but climate simulations provide a consistent message:

Global warming will not change Northwest summer precipitation by much, perhaps with a very slight decline in the west that will hardly be perceptible. And east of the Cascades might get wetter as more southwest monsoon moisture moves northward.

Now temperatures will warm slowly during this century, which will cause more evaporation, so soil moisture during summer could well decline. But there is no abrupt, end of the world, "existential" drought threat in the offering.

Sometimes atmospheric variability randomly gives us a very dry summer, like this year, but that is entirely natural and expected.

Any media or individuals telling you otherwise is not following the science.