When many people think of wildfires, they often first visualize a forest fire.

And when the media and politicians talk of wildfires, they usually hone in on drought and climate change as the cause.

But if one is interested in the wildfires that kill and injure the most people, or wildfires that do the most economic damage, forests and drought are not the key factors.

In reality, it is grass and wind, which can produce rapidly expanding grass/range fires that have resulted in billions of dollars of loss and the deaths of many hundreds of individuals.

As described below, grass/range fires are the main threat to humanity. And there is much we can do to reduce the terrible impacts of these events using the best science, technology, and land management.

Note: The term rangeland includes tallgrass prairies, steppes (shortgrass prairies), desert shrublands, woodlands of small shrubs, savannas, chaparrals, and tundra landscapes. Such vegetation often desiccates during the warm season (or under temporarily dry conditions).

Some Examples of Major Grass/Rangeland and Wind Fires- The 2023 Maui wildfire in which 60-90 mph winds descended the West Maui mountains and resulted in electrical fires that spread through fields of flammable grasses into Lahaina. Over 100 lost their lives, with billions of dollars of direct and indirect loss.

- The 2018 Camp Fire that destroyed the town of Paradise, California, resulted in 85 deaths and over 16 billion dollars of damage. Strong winds descending the Sierra Nevada caused electrical fires that spread on grass/range vegetation (and some trees) rapidly toward the town, with little warning.

- The 2022 Marshall Fire, when strong winds descended the Colorado Front Range, pushing a grassfire into Superior Colorado, killing two and destroying over 1000 homes. Damage is estimated to exceed two billion dollars.

- The September 2020 Malden (WA) Fire, in which powerful northerly winds resulted in sparks from the broken powerline that ignited range vegetation that surged into Malden, destroying most of the town.

- The October 1991 Tunnel Fire, in which strong easterly flow resulted in a grass/range fire that destroyed nearly 3000 homes and killed 25 near Oakland, CA. 3-5 billion dollars in damage.

The Marshall Fire Burned Through Grass into Superior, CO. Picture courtesy of Tristantech.

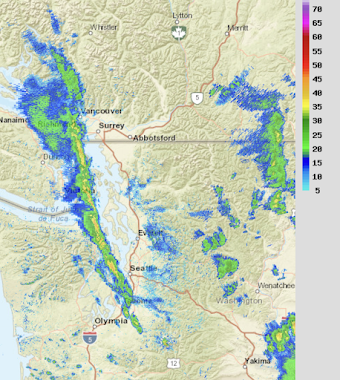

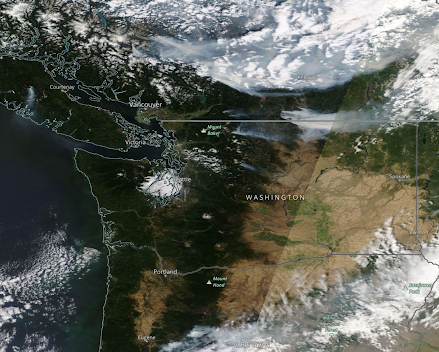

The largest fires this spring/summer in Washington State were grass/range fires (see map for eastern WA).

I could provide you with dozens of other examples, but the message is clear: the overwhelming majority of wildfire deaths and the bulk of the economic loss from wildfires are associated with grass/range vegetation and strong winds.

Grass and Range Fires

Grass and range fires occur in light fuels: grasses, small bushes, and the like. They often go through a distinct seasonal cycle: greening up during the cool/wetter winter and then drying out, with the foilage above the surface dying (see picture above).

Grasses and small vegetation (less than 0.25 inches) are 1-hr fuels, which means they can dry out within roughly an hour. Small bushes are 10-hr fuels.

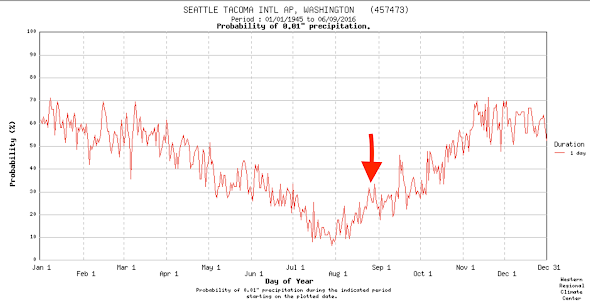

The fact that such vegetation can dry out very quickly under the right conditions (no precipitation, lower humidity, strong winds), means the previous weather/climate conditions are of minimal importance.

Even if it rained the day before, they can rapidly dry out to support fire. Particularly, with strong, dry winds, these light fuels will be ready to burn quickly. So prior "drought" in the weeks or months before is pretty much immaterial.

What can increase the risk of range and grass fires is above-normal precipitation during the previous spring and winter, which results in more bountiful grass growth. Thus, drought the previous winter would REDUCE wildfire threat, a subtlety absent from most media stories.

Rangeland in Hawaii. Picture courtesy of Aaron Yoshino

Wind and Grass/Rangeland

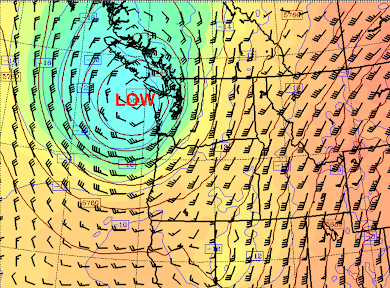

Wind plays a huge role in grass/rangeland fires. Once the fires are started, strong winds provide huge amounts of oxygen for the fire, and rapidly push the fire forward by moving hot embers and superheated air ahead of the flame front.

Wind can also help dry the light fuels, by greatly enhancing evaporation. Dry winds are particularly good at very quickly drying grass fuels.

This is why strong downslope winds are the absolute worst situation. As the air descends and accelerates down the slope, it is warmed by compression, and the relative humidity plummets.

Thus, many of the great wildfire disasters (Maui, Marshall fire in Colorado, Camp Fire west of the Sierra Nevada) are associated with downslope windstorms.

It is important to note that there is no evidence that winds are increasing or downslope windstorms are becoming more frequeny due to climate change. In fact, the opposite is suggested on the West Coast, where substantial research suggests that warm/dry easterly flow down the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada and Cascades will WEAKEN under global warming.

The Grassland/Range Wildfire Situation is Getting Worse--And it is NOT Because of Climate Change

Grass/range wildfires driven by wind have always been serious threats, but deaths and damage from them are increasing. Climate change is not the reason.

First, much of the western U.S. and Hawaii have been invaded by non-native, invasive, and highly flammable grasses. One of the worst is cheatgrass, which is now found extensively around the nation (see map).

In Hawaii, invasive, flammable grasses have invaded agricultural lands that have been abandoned during the past few decades, resulting in huge flammable areas next to densely populated areas (see map below)

But the increase of vast areas of flammable vegetation is only part of the problem.

Increased population has resulted in far more powerlines, which are providing a potent ignition source of fire when winds are strong.

And increasing population near and in grasslands has resulted in hugely increased vulnerability to grass/range fires.

Finally, increasing grassland/range fires also results in increased forest fires, because grassland and forest are often adjacent and intermixed, and grasses/shrubs extend into forest areas. Grass/range fires can move into forest areas, where the fire can ascend into canopies through a variety of ladder fuels.

Dealing with the Threat of Grass/Range Wildfires

There is much we can do to lessen the threat of grass/range wildfires. We can save many lives and greatly lessen the damage from such fires.

But to do so requires that society deals with the real origins of the problem and attack the problem in a rational, science-based way. In this final section, I will describe some approaches that can help.

Use Weather Prediction and Fuels Information Better

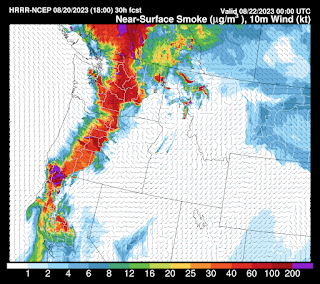

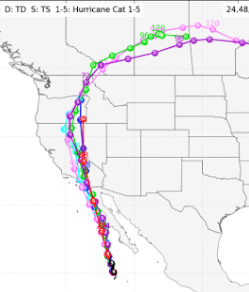

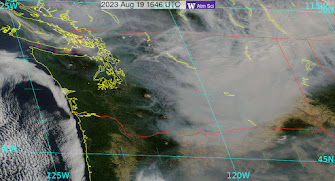

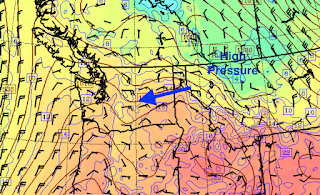

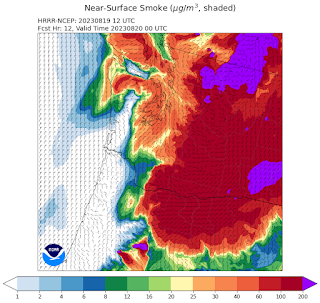

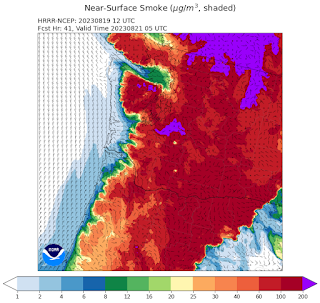

During the past decade, the ability of high-resolution weather forecast models to predict the conditions associated with wind-driven grass fires has gotten stunningly good, specific in both time and space. But this valuable information is often not effectively applied

For example, numerical prediction models clearly forecast the extreme winds and low relative humidity associated with the Maui fire (see my previous blog on this). But little of the extreme threat near Lahaina was communicated.

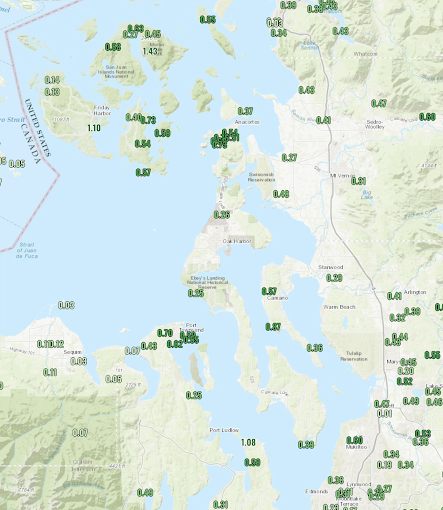

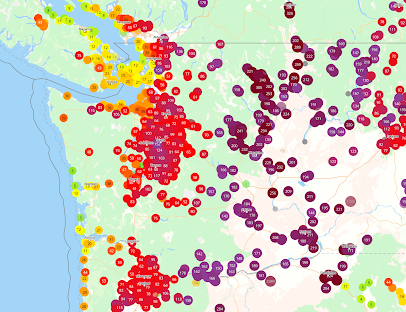

In addition, satellite-based observations coupled with machine learning now provide real-time maps of where range-grass fuels are available in dangerous quantities (see the wonderful USDA Fuelcast site graphic below)

By putting the two data sources together (predicted winds and available dry fuel), we can provide very timely warning of wildfire threats.

Let me be very concrete here. Wildfire Prediction Centers should be established for Hawaii, Alaska, and the lower 48 states to provide such guidance, as well as to interact with local authorities and power companies.

The National Weather Service and other agencies must become much more aggressive in providing specific and timely warnings of this threat.

Deal with the Electrical Infrastructure Problem Through De-Energizing and Hardening Powerlines

Let's be frank. Many of the most deadly and destructive grass/range fires have been caused by failing powerlines, which cause sparking that easily ignites the "kindling" of dry grass/range vegetation.

In many areas, power infrastructure needs extensive and expensive remediation.

Until we can harden the current power infrastructure, much more aggressive de-energization of powerlines is required. Fortunately, high-resolution weather prediction and knowledge of the state of the surface fuels can allow such power shut-offs to be limited in time and space.

Creating Fire Breaks around Range/Grassland Areas Near Populated Regions, Reducing Grass Load.

Firebreaks can be created near population centers, and grazing animals and mechanical cutting can be used to reduce fuel density, among other steps.

Improved Construction in Dangerous Areas

As clearly shown by the Maui, Marshal, and Camp Fires, homes and buildings take over as a fuel source as grass/range wildfires reach urban areas. Non-flammable roofs, screens to prevent invasion of firebrands/embers, removing vegetation near buildings, and other steps can make a huge difference. The lone house to survive in Maui was a stark illustration of the ability to reduce risk.

The Bottom Line: Grass/range fires are the major cause of wildfire deaths and economic loss in the U.S. Such fires generally result from seasonally dry fuels and strong winds. Since the dry fuels can be monitored and the winds skillfully predicted, the potential for large and rapidly expanding grass/range wildfires can be forecast in advance with some skill. Climate change has little to do with such grass/range fires. Many steps can be taken to reduce the grass/range wildfire risk.