To what degree is anthropogenic global warming contributing to Washington State wildfires?

If 90% of the blame for Northwest wildfires is due to anthropogenic (human-caused) global warming and 10% is due to fire suppression, poor forest management, or people starting more fires, then the logical response is to put most of our efforts into reducing atmospheric CO2. A climate-dominated problem.

If 90% of the blame is due to past fire suppression, forest mismanagement, invasive species, and human encroachment, then we should put most of our efforts into fixing the forests and other non-climate measures. A surface-management problem.

And yes, the percentages could be somewhere in between.

Supporters of the carbon fee initiative (1631) are suggesting that the recent wildfires are mainly the result of anthropogenic climate change and using the fires to push their carbon fee plan.

And Governor Inslee has stated explicitly that the fires have been made much worse by climate change.

In contrast, others, including a number of folks in the forestry community, have suggested that poor forest practices are the main cause of most of the wildfires over the eastern side of the state.

It is important to note that relative role of global warming in influencing the threat of wildfires may change in time. For example, global warming could be relatively unimportant today for wildfires, but of great importance later in the century when temperatures will be much warmer.

The Need for Better Information

There is actually very little limited quantitative information on the role of global warming on Washington State wildfires. Which is kind of strange considering the importance of the issue and the authoritative statements being made by some. A lot of hand waving, but not much data.

So let's examine the issue in some depth, using a more quantitative approach than most. But before I do so, let me give you the bottom line.

Human-caused global warming has played only a minor role regarding Washington State wildfires through today, but will become much more important later in this century.

Now let me provide some evidence for this conclusion.

How Has Global Warming Changed Washington's Summer Climate?

Before we look at the correlation of global warming and wildfires, we need to know how much Washington State climate has changed during the past half century or so, and then estimate how much of that change is due to anthropogenically forced increases in greenhouse gases. To gain some insight into this, I secured the official NOAA/NWS climate division data averaged over Washington State for summer (June through August).

First, consider daily mean temperatures from 1930 to today.. Very little warming until the mid-70s and then perhaps 2°F overall during the past 40 years.

Summer average maximum temperatures have similar pattern of change--again roughly 2F warmer since the mid 1970s.

There is a substantial research that suggested that the radiative effects of increasing CO2 in the atmosphere became significant for climate forcing something around the 1970s. And there was an important shift in a mode of natural variability, the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PD0) during the mid-70s: a shift from the cool to warm phase of this oscillation, which would have resulted in warming over the Pacific Northwest.

Now the question is how much of the recent warming shown above is due to anthropogenic global warming and how much is due to natural variability.

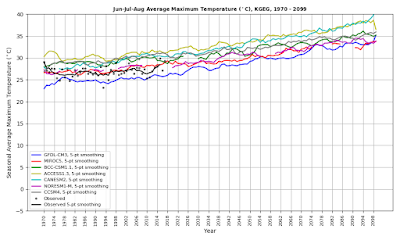

A group of researchers at the UW (including myself) are working on this question, using the most sophisticated approach applied to date: an ensemble of high-resolution regional climate runs forced by the best global models. This is the gold standard for such work. We started with global climate models driven by the most aggressive increase of greenhouse gases (RCP 8.5) and then ran a high-resolution weather prediction model (WRF) driven by several climate models over time (1970-2100).

I don't have this output interpolated to the exact boundaries of WA state (working on this now), but let me show you the projections for summer max temperatures from the high-resolution model for two sides of the state (Hoquiam, HQM, and Spokane, GEG) forced by several climate models (see below in colors). I also show the observed temperatures during the contemporary period at these location). Virtually all of our simulation show greater warming at Spokane then along the coast, so let me show you that first.

Between 1970 and roughly 2000 there is very little change in observed or modeled temperatures at Spokane, and roughly1.7F warming between 2000 and now in most of the simulations. Since natural variability will differ between the simulations, the 1.7F average of all of the runs is a reasonable estimate of the impact of global warming until now. And note how the warming revs up later in the century if the aggressive increase in greenhouse gases continue s(about 7F warming!).

At Hoquiam, near the WA coast, the warming is less for both the recent decades and into the future. Perhaps 1F of warming through this year.

Now, I could show you a lot more material, but my conclusions from looking at a lot of high-resolution model data is that anthropogenic global warming due to increasing greenhouse gases may well have warmed up the state as a whole by roughly 1-1.5F during the past half-century, with any additional warming coming from natural variability (e.g., the PDO). I really doubt that there would be much disagreement about this estimate from members of the atmospheric community.

What about changes in precipitation?

Summer (June to August) precipitation has always been relatively modest (4-5 inches) in our state (our summers are very dry), and there appears to be a modest wetting trend through 1980 and some drying since the late 1990s (see below). In contrast, annual precipitation has been very constant (also below)

|

| Summer Precipitation for WA State (1930-2017) |

|

| WA State Annual Precipitation |

What do the climate simulations suggest about precipitation trends?

The annual precipitation will slowly increase according to the models (not shown), but what about summer? Spokane summer precipitation has always been low (around 2.5 inches typical for June through August) and will remain low. Any decline is small--a half-inch at most. The recent dry years look like natural variability.

Let's compare that to Seattle on the western side of the State. Summers are equally dry as Spokane, but there is a more clearcut drying-- by roughly 2 inches by 2100, and perhaps .5 inches during the past years. These results are consistent with previous studies by the UW climate impacts group and others indicating a slow increase of total annual precipitation, but a small downward trend in summer precipitation over our area.

So to summarize. Looking at past climate data and the best model information, one concludes that increasing greenhouse gases may well have warmed out state by 1-1.5F during summer (June through August) over the past half century, had little impact on annual precipitation, and perhaps dried an already very dry summer by perhaps .5 inches.

But how did global warming impact the recent wildfires in Washington State? And how will future warming impact them?

We are now ready to answer this question.

But first we needed a list of the annual area burned and number of fires in Washington State over time. It turns out this is a difficult information to get--which is surprising considering its importance. I was able to get an Excel file from Josh Clark of WA State DNR with the fire information from 1992 to the present. The prior period has not been digitized, with fire information in cabinets somewhere. Oregon and California has done a better job in creating a long-term digital record of their fires.

OK, we will use what we have. Here is the number of acres burned by wildfires over WA state since 1992. A very slow trend upward, except for the HUGE peak in 2015, the year with the big ridge and crazy-warm spring.

The number of fires (see below) have been nearly constant in the long term, with some ups and downs/

But now the really interesting part. Let's plot the acres burned against warm season (June through September) temperatures (see below).

This is really fascinating. A very slow increase of fire acres with temperature, with considerable scatter, showing that acres burned is not that temperature sensitive. The one big year was the warmest.. 2015 with 61.4 F and nearly 1.2 million acres burned.

The bottom line of all this is that warming temperatures can explain only a small portion of the variability in Washington wildfires.

What about precipitation? Here is the plot of WA state precipitation for May through Sept since 1992. A very slight downward trend, with the big fire year (2015) not showing anything anomalous.

Another "scatterplot", this time of acres burned versus precipitation, is presented below. Very poor relationship, with the suggestion of a decline in burned acreage with greater rainfall. And the precipitation only explains about 2% of the variability of acres burned! This is not surprising because our region is naturally dry during the summer and being a little drier doesn't make that much of a difference. Like being a little more dead.

The Essential Message Here

Climate/weather changes do affect wildfires over Washington State. Warmer temperatures and lesser precipitation correlate with increasing acreage, but the relationship is not a strong one. The correlation of summer precipitation with wildfire acreage is very, very weak and summer temperature only explains less than a quarter of the variability in wildfire area.

Then we look at the look at the amount of climate change produced by human-caused greenhouse warming so far, and we find it is relatively small. Perhaps 1.5F for WA State temperatures and a slight drying over the summer.

You put the lack of sensitivity together to temperature/precipitation with the small climate changes due to global warming and one has to conclude that human-caused climate change is undoubtedly NOT a major driver of the increased wildfires and wildfire smoke we have seen during some recent years.

Based on my extensive reading on the wildfire issue, discussions with forestry experts at the UW, and a number of seminars/meetings I have attended, my conclusion is that the real culprits for our invigorated fire/smoke situation include:

1. Nearly a century of fire suppression and poor forest management that have produced unnatural, explosive forests, particularly on the dry side of our state.

2. Huge influx of people into the urban-wildland interface and forest areas that help initiate fires and make us more vulnerable to them.

3. Invasion of highly flammable, non-native species like cheatgrass.

And we should not forget that fire is a natural part of our east-side forests.

Claiming the climate change is the big villain in the current wildfire situation, may be a useful tool for some ambitious politicians and for those searching for arguments to support climate-related initiatives, but the truth is probably elsewhere. In the FUTURE, as temperatures warm profoundly (particularly during the second half of the century), the influence of human-produced global warming on our wildfires will clearly increase substantially.

Only by a sober, fact-driven approach, such as thinning, debris-removal, and proscribed burning of our east-side forests, with will be able to improve the health of our forests and reduce the potential for megafires and big smoke production. Even if we could stop anthropogenic climate change in its tracks this year, we still need to deal with the issues of forest management, human initiation of fires, and human changes at the surface.

PS: Although we had considerable background smoke from Canada, the really extreme smoke periods (August 21-22 in Puget Sound) was associated with fires over NE Washington, not Canada. Same thing in 2017, with WA fires resulting in ash falling on Seattle.

PSS: Some folks might bring up the Pine Beetle issue. I have read several papers and talked to experts in UW Forestry that suggest that rather than lack of cold temperatures, unnaturally dense east-side forests and lack of fire allowed the Beetle kill. In any case, peer-reviewed papers suggest that pine beetle infestation does NOT contribute to fires.

____________________________________

A local forest landowner named Michael August has written a very interesting perspective on NW forests and smoke, found here.

I live on Puget Sound, facing east, to Canada. I have the impression that by far and away most of the smoke is now produced in British Columbia. Hopefully more and better data will become accessible on Washington state, as Dr. Mass mentioned. But I hope our analysis of what's going on will include a major focus on B.C. as well. My understanding is that a lot of it is trees killed by beetles. But what is causing an increase in the beetle count?

ReplyDeleteYour analysis is trusted and appreciated.

ReplyDeleteA very good run-down of the current situation, and (if I'm reading it correctly) a "visible but probably less than a 20%" influence from anthropogenic global warming upon the fires.

ReplyDeleteIf I'm overstating that number, please correct me.

Then you tantalizingly wrote: "In the FUTURE, as temperatures warm profoundly (particularly during the second half of the century), the influence of human-produced global warming on our wildfires will clearly increase substantially."

Could you kindly hazard a "contribution percentage" number on that "substantial increase" for 7F by 2100? You're certainly welcome to give your number a confidence value, too.

Thanks

You'd have to analyze fires in B.C. and maybe Oregon to make this conclusion, as the smoke in Washington came across the border.

ReplyDelete"You put the lack of sensitivity together to temperature/precipitation with the small climate changes due to global warming and one has to conclude that human-caused climate change is undoubtedly NOT a major driver of the increased wildfires and wildfire smoke we have seen during some recent years."

Some smoke blew west from Eastern Washington this summer, where fires were burning, but even some of that smoke came from Canada.

Cliff, while i doubt anyone can quibble with the technical facts as you describe nor the general exaggeration of climate change effects so rampant in the headlines, your prescription for solutions is by your very own words contradictory.

ReplyDeleteYour introductory statement concludes:

"If 90% of the blame is due to past fire suppression, forest mismanagement, invasive species, and human encroachment, then we should put most of our efforts into fixing the forests and other non-climate measures. A surface-management problem."

yet your summary states:

"In the FUTURE, as temperatures warm profoundly (particularly during the second half of the century), the influence of human-produced global warming on our wildfires will clearly increase substantially.

You seem to be suggesting that current risks only should influence our current actions. Future risks will be adequately dealt with by future actions. In other words, there is nothing we should do now to effect future risk. By this standard no one should be seeking to transition away from fossil fuels because the warming that is now occurring is not what can be characterized as either fossil fuel caused or "catastrophic" in nature and if it is fossil fuel caused and catastrophic in the future, that is when we should react to it.

Forgive me if I'm missing something but as I understand it, climate change risk is entirely a forecasting problem. The only known solutions must occur now and be sustained for years to positively influence hazards that will only significantly arise in the future. If we wait to experience the catastrophic potential of climate change before we implement mitigative actions, it will be too late for any action but adaptation and geo engineering, both being highly speculative and hypothetical as to a successful outcome under the expected warming even by mid century.

As well, by the framing you give the problem - forest fires only, the pacific northwest only - it neglects to point out that northwest fires will not be occurring in isolation of all the other ecological changes that are either expected or will surprise us, on a global scale not just in the northwest.

I'm pretty sure you didn't mean to emphasize this but I hope in retrospect you can see how this could result as the message by your choice of phrasing and language.

The linked article by Michael August at the end of this article is must reading for anyone with an interest in this subject. Michael touches on a little known factor in the size of large fires in the western US with the reference to a single overnight 8,000 acre backfire in California: firefighter "firing" activities burn large portions of the actual burn acreage. The 2002 Biscuit Fire in the Kalmiopsis Wilderness in Oregon is claimed to have up to 50% intentionally burned.

ReplyDeleteAdditionally, according to statistics from the NIFC in Boise, many states routinely burn more acreage in prescribed (Rx) burns than from actual wildfires, and the amount is increasing rapidly. Washington State does not see a lot of Rx fires from state and federal agencies, but as recently as 2011 (a quiet fire year) we had less wildfire acres burn than prescribed burns.

Pine beetle infestation eventually causes alot of deadfall to be on the forest floor. This alone may not cause a fire but it will certainly make the fire more intense and larger because of the dead and dried fuel on the forest floor. The Tweedsmuir complex fire in west-central BC was the largest fire this year in that province (and produced much of the smoke that we saw) and it burned in a large area of beetle kill. Furthermore, the Chilcotin region, which has seen numerous massive fires over the past decade or so was, coincidentally, one the worst hit regions in regards to the pine beetle. The fires there started getting larger and more intense as soon as the beetle kill occurred. In fact, there isn't much beetle kill forest left to burn in that region as there have been so many massive fires in the beetle kill lodgepole pine forest.

ReplyDeleteCliff I always appreciate your analysis and insight. However, I am always left wondering if it is complete. As a simple example, "Unknown" above talks about beetle kill of trees. The effects of insect damage are out of your wheelhouse and so get ignored in your analysis. The beetle populations may be very sensitive to temperature/precipitation effects. The tree's resistance to beetles may also be influenced by such factors. This is just an example to show that the question is really a multi-disciplinary one. I fear that the same weakness applies to the general climate models you refer to in this post. As an example what do your models assume for the vegetative albedo as the climate warms. How sensitive is the model to changes in vegetative types? The same for algae and bacteria populations on the ice and in the oceans. You have explained many times that the meterological community validates the models against previous climate changes to see if they can predict them. I have always been a fan of the idea, in systems thinking, of punctuated equilibrium. It is my prediction that is what we are going to get. Likely most of us will get to find out!

ReplyDeleteI want to offer my 2 cents worth on why so many people, including one professional meteorologist I know, are reluctant to say that humans are causing the climate to change.

ReplyDeleteIt's all psychology: If you can convince yourself that it's purely a natural phenomenon (and it is difficult to PROVE that humans are causing it) then you and society are absolved of all responsibility.

But as soon as you admit to yourself that we (collectively) are responsible for the problem, or a large part of it, now you not only guilt-trip yourself, but you obligate yourself and society to do something. Which, of course, will, at least in the short run, cost money and perhaps reduce our the standard of living.

Eventually, of course, we'll all benefit from taking action, because the clean energy sources are, by and large, the "eternal" sources (solar, wind, possibly nuclear fusion, etc.) but, unfortunately, humans are wired to think short term. We think about next month's rent or next year's tomato crop, but not about the hurricane or the earthquake that might come in 5 or 50 years- or how the climate is changing.

Unknown,

ReplyDeleteThey say it is global warming- once again. If I am not mistaken, in the interior west where the beetle problem in most acute, the winters are warming faster than the summers. I read that it takes several days of temperatures as low as -30 degrees F. to kill the larvae. As a child I remember hearing about low temps in winter- minus 40 in Minnesota, or minus 60 in Montana. But we rarely hear about extreme cold snaps these days. What grabs the headlines? Heat, smoke, earthquakes, hurricanes, tornadoes, and occasionally winter storms- but rarely just plain severe cold.

Maybe if we are lucky, mother nature will provide an alternate natural control for the beetle problem- and they are admittedly native beetles. Millions and millions of woodpeckers, perhaps. We can hope.

"I have read several papers and talked to experts in UW Forestry that suggest that rather than lack of cold temperatures, unnaturally dense east-side forests and lack of fire allowed the Beetle kill. In any case, peer-reviewed papers suggest that pine beetle infestation does NOT contribute to fires."

ReplyDeleteThere you go again, using peer - reviewed studies that don't conform to the dominant meme. A long time friend has worked in forestry for decades, and he said the same thing when I asked him about the beetle infestation in the Inter - Mountain West, which began over two decades back. Clinton put a virtual moratorium on any planned fires and/or culling in the National Forests, and that policy has not appreciably been altered until recently. I grew up a Cub and Boy Scout, and the one thing we always believed was that any fires were bad, and Smokey the Bear was a saint. How wrong we were, but...science said so!

I would think that the number of lightening strikes in any given summer would have a significant impact on wildfire frequency. Now that we are able to monitor lightening strikes it will be interesting to see if a trend develops as the climate warms.

ReplyDeleteI agree with Bruce Kay's point. As with investing's#1 most ignored truism (past returns are no predictive of future returns), I think we'd be wise to appreciate and NOT ignore that truism for future effects of climate change.

ReplyDeleteI also agree totally with Cliff's consistent point that more people living in the urbanwild interface, totally unrestricted by sane zoning laws, is crucial and apt to become even more problematico as more people flock to Pacific NW ISO a region that its claimed will be "less impacted" in the short term (current lives) by climate change, rising sea levels etc.

So I admit I don't take any comfort in finding that 'so far' climate change has maybe contributed only a 'little, maybe 20%?' to PNW wildfires (not disputing data or analysis here). Knowing that only one room, say 5%, of a house is on fire so far doesn't mean the whole home isn't threatened.

I wonder how R^2 would be changed if 2015 (an outlier) was removed?

ReplyDeleteYour blog seems to be sending mixed and unclear messages. As the climate mean temperature slowly rises, so do the climate extremes. Hurricanes and wildfires are associated with the warm extremes or anomalies in the weather and ocean variability, more than the means. In your analyses you always show and discuss the climate means, but rarely discuss the impact of the extremes on the phenomena at hand. In this blog you you imply that there is no need to put effort into reducing CO2 because that is not the cause of the increasing wildfires and yet you concede that wildfires will increase dramatically in a warmer climate at the end of the century. Assuming that is the case, isn't now the time to address the issue of rising greenhouse gasses? If we wait won't it be too late?

ReplyDeleteCliff - What about regressing against the synergistic interaction of temperature x precipitation? You might find that something like vapor pressure deficit or potential evaporation explains a much higher percentage of variation in fire acreage than either alone.

ReplyDeleteAs I understand it, Cliff's now long running criticism of the Media and politicians is not so much their message that risk from climate change is growing larger and will become significant eventually, it is that they are defeating themselves by exaggerating the current attribution simply to excite an interest and concern in the absence of any. In other words while the intention is good, the process of persuasion employs a fallacy, one that is more saliently motivating than "the truth" can ever be.

ReplyDeleteIt is really hard to argue with this point. Logical fallacies, essentially invalid heuristics, are indeed cognitive illusions that are used to illicit very specific judgement and decisions where the literal facts will fail. We know that the literal facts of anthropogenic climate change do very much fail to illicit much in the way of will and commitment from most of us to lift a finger to change anything so I think no one should be too surprised that some stretching of the truth will pop up in the debate.

That certainly doesn't legitimize it in an ethical sense. We just can't abide being manipulated by falsehood, even - or maybe especially - if its just a vaguely plausible exaggeration. This is what we tell ourselves but as you can see, this exaggeration of the current climate change influence on fires is not as offensive for some as it is for others. It all depends on where your biases lie to start with. What motivates us politically, not factually, determines the level of our outrage at this sleigh of hand.

Indeed Cliffs Blog articles can also be viewed as "vaguely plausible exaggerations" by exactly the same standards of rhetoric. Not so much his arrangement of the numbers (to paraphrase Mark Twain) but the meaning he attributes to those numbers in terms of risk management. To say that "not much of the present day wildfires can be ascribed to climate change, so the majority of our mitigations should not target climate change" is a curiously strange emphasis considering all that we know about our obligation and ability to mitigate much, much more than just the present day fire risks of little old North west United States.

What is important in these motivated narratives is what is left out of them - if indeed it is left out. If the "Climate change is causing Forest fires" drum pounders can see fit to qualify their hysterical headlines with at least some reference in the main body of their text to what the real experts are actually saying, then maybe Cliff in some future Blog will also stray from the naughty deceptive media narrative and perhaps help them better frame the problem of risk - and while your at it, moral obligation - in a narrative that also better approximates what the experts are saying about that.

I found the PDF by Mike August, appended to your 9/302018 blog, on the fire fuel problem on the east slope of the Cascades was especially interesting. I would like to send this to several others who might also enjoy it. Can you provide contact information for him?

ReplyDeleteThanks, Charles Heebner

Steve,

ReplyDeletePerhaps I am not being clear. Of course, we should reduce CO2 emissions because later in the century the warming will be enough to contribute to more and larger fires. But the contemporary fires have little to do with global warming. And the drying of the fuels takes time...that is why the means, rather than the extremes are critical. ..cliff

bev and charlie...send me your email and I will pass it on to Mike August...cm

ReplyDeleteJonathan Ursin....a very perceptive comment. Getting rid of the outlier would greatly reduce the r2 values...about halving it...cliff

ReplyDeleteThat's all fine, but 2F increase corresponds, roughly, to 1C increase in temperature which is what is acknowledged to be the practically sure-fire amount of anthropogenic warming (it may be more, but that's not established). Additionally, the wild outliers in the scatterplots raise questions (I don't have answers, but, still, you know, fat tails and other "rare events" that invalidate Gaussian models). More generally, linear regression seems a poor summary of a complicated picture, but we know that weather is a chaotic system, don't we?

ReplyDeleteI see an exponential curve riding the peaks rather than a recent outlier.

ReplyDeleteLet's see an article about the massive cold influx coming through the western part of the country and eventually the east. Canada has been inundated for a while now with cold, and we've been cooling for over a month. Let's get to the winter and have a little less of hanging on to the small summer we just had. Cheers Cliff.

ReplyDeletemeerkat - good eye! However to be soberly objective we need to confirm that hypothesis by waiting patiently to see if that curve plays out.

ReplyDeleteOh wait a minute. That may be the academic solution...... but is it the risk management solution?

Thanks for this informative article, and the discussion it provokes. We need to mitigate these smoky summers, if humanly possible. I agree that global warming is only beginning to manifest itself in drier, more fire prone conditions.

ReplyDeleteThe terrible fires in California are a sober reminder that living near the woods can be dangerous and costly. Also to be addressed is the role of high-power lines creating these fires during the dry season when the Santa Ana winds are rampant.

Cliff,

ReplyDeleteYou, as usual, bring important reasoned perspective to this important issue that effects us all. Your discussion of temperature in particular I find interesting; not as much for the data presented, but for the data not presented. I have read from several scientifically peer-reviewed sources now that the rise in night time temperature lows is likely a significant contributory factor to our wildfire situation. Specifically, night time humidity recovery is lower and fuel moisture is reduced accordingly. That said, having worked as a biologist for the USFS for many years here in the PNW, there is little doubt that the greatest contributory factors are poor management, WUI encroachment, and annual grass invasions. Could you comment on the night time temperature issue?

Absolutely powerful article covering both sides of the issue! One observation on my part: for those who insist that global climate change (or, is it global warming?) requires that we need to do something NOW (including taxing us into mass transit as the only way to get from point A to point B) are the same people who insist that forest management is nothing more than man's way of intruding on nature and block said approach at every hand. Until there is a meeting of the minds to do both, what we have seen in recent years will continue to be the new 'norm' in our future. In that case, the old adage holds true: there are those who truly can't "see the forest for the trees" when it comes to reasonable solutions for protecting our environment.

ReplyDeleteSo it looks like the key estimate from the regression model is that the 1.5° of anthropogenic temperature rise over the past century accounts for an additional 140'000 acres/year burned. That seems quite significant compared to an average of ~213'000 acres/year burned. I find that explaining 22% of the burn area with just temperature is quite high (since random year-to-year variation is definitely the dominant factor). I'd be surprised if any of the non-climate related factors you mention are as significant as the climate contribution.

ReplyDeleteI watched this linked video recently, How Fighting Wildfires Works, and it mentioned mismanagement of natural forest fires. The video is well done and efficiently communicates a lot of information which I have also read about on this blog. It is definitely worth 10 minutes of your time if you are curious about wildfires.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EodxubsO8EI

Purely coincidental, i'm sure ... Oct 2nd's Nature Communications has an open-access paper looking at the projected effect of global warming (1.5, 2 and 3 C) on European forest fires.

ReplyDeleteTheir conclusion: 1.5 C will produce 40% more burn area, and 3 C will make it 100%.

The paper is "Exacerbated fires in Mediterranean Europe due to anthropogenic warming projected with non-stationary climate-fire models", by Marco Turco et al.

Direct link: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-06358-z

Have you discussed the recent paper "The Nature of the Beast" with the Forestry people who wrote it. The paper argues controlled burning or thinning is not workable on the west side of the mountains.

ReplyDeleteBev and Charlie, Ginnaville-

ReplyDeleteThank you for your comments.

On the matter of increasing back firing acreage totals, several issues make an "indirect attack" is an appropriate strategy. True, the tactic can increase the total acreage of a fire, but topography, fuel type, local weather and burning conditions can dictate it for firefighter safety.

Another factor involved is that when fire season gets going, firefighting crews and equipment become scarce. An indirect attack can allow for containment with limited resources. In cases where homes or development are at risk, losing a few thousand more acres can be easily justified.

Liability. Fire line supervisors engaged in suppression activities are increasingly wary of direct attack because of exposure to lawsuits when fatalities occur. The Forest Service does not necessarily indemnify line personnel against financial judgement when criminal cases are brought against fire line supervisors. The threat of financial ruin has seen line supervisors purchasing liability insurance on their own dime. As a result, there is an growing reluctance to go "direct" when folks may shoulder the burden of a lawsuit when things go awry in a dynamic environment. Hence, they back off a ridge line or two, put in a bulldozer or hand line, and then backfire or burnout the unburned fuel between their line and the fire. Heavy slash or flashy fuels on steep hillsides might be a circumstance where the approach is appropriate. Hence, acreage totals are increased, but firefighter safety is enhanced.

This practice is becoming more the norm, however. I can recall countless shifts 'back in the day' building fire line downhill at night on steep ground, both situations that "Shout Watch Out!" For good reason. Darkness reduces situational awareness. For example, one cannot see falling trees or boulders rolling down the hill loosened by fire. Injuries sustained from these objects can be life threatening, if fatal. That said, burning conditions at night allow for more direct strategies and reduced acreage totals. Direct versus indirect approaches are situational and conditional.

Feel free to contact me directly with any questions or comments-

Mike August

michaelmaugust@gmail.com

"Young Men and Fire" by Norman Maclean is a seminal book on a disaster regarding firefighting methods of the day. We're still learning how to manage our forests to this day, unfortunately.

ReplyDeleteCliff, several observations on your analyses. Errors in my previous post corrected here.

ReplyDelete1. Analysis timeframe. Your summer temperature analysis shows that there is no real change in temperature until the mid-seventies and a gradual increase since then. Similarly, for summer precipitation, you note a slight increasing trend through the 1980s, and then a decreasing trend since the 1990s (I will come back to why this may be important later). But when you plot summer temperature against acres burned, you use all the temperature data from 1930 to present, including the earlier data where there was no real trend in summer temperature. If the hypothesis that you are testing is that fire frequency or fire intensity are linked to changing temperature, why analyze data for a period where you acknowledge there is no temperature signal? No wonder the R2 is low for this analysis. All things being equal (I.E. poor forest management practices in place over much of the period, from at least the 1960s to present), such a broad temporal range of analysis with lots of data having no temperature trend or signal would not likely show any relationship of acres burned to temperature, allowing other factors to dominate variability.

2. Thaw timing. You did not consider potential shifts in spring thaw, and changes in snow pack and seasonal snow pack cover over time in your analysis. These parameters affect soil moisture content through the summer in eastern high elevation forests, which will affect burning conditions, and may not be directly correlated to summer air temperature or summer precipitation. Including such parameters in your analysis as shifts in seasonality and soil moisture that are likely related to the leading edge of climate change would seem a better proxy for how global and regional warming is priming forests to burn compared with summer precipitation and temperature. Earlier snow melt would start the forest floor drying process earlier and likely result in lower summer soil moisture content. As with temperature, snow melt has likely accelerated recently, but may have a tighter correlation with acres burned.

3. Winds. Regardless of whether we are experiencing increased susceptibility to fires regionally, how we experience those fires in western Washington is certainly changing, with the source of the smoke coming from the north, east and south. I do not remember experiencing the recent glut of smoky summer days in Western Washington over the previous half century. Either there are more sources of smoke upwind of our region, or there is a change in wind direction or intensity that is now carrying more smoke to Puget Sound and coastal areas. Are the shift in winds resulting in reduced summer precipitation, increased summer temperature and increased smoky days in the state? Is a shift in prevailing winds also an outcome of climate change? Is this what we have to look forward to nearly every summer now?

4. What to do. Finally, scientific literature suggests climate change is driving an increase in the destructiveness of wild fires in places like northern California, our area is suffering from poor air quality and smoke filled skies, and you admit that your modelling and analysis efforts predict significantly greater risk of wildfires in the future. Given this information, taking actions like those in 1631 that immediately and directly reduce carbon emissions here, and indirectly influence by societal example carbon emissions elsewhere in our country and the world, will likely have a positive impact on our regional air quality and the integrity of our forest ecosystems and infrastructure. Sure, let’s manage our forests better, but let’s not bury the recent signals and impacts of climate change in analyses of years of data collected under a very different atmosphere and ocean CO2 and heat regimes than we are experiencing now.

5. In summary, I am not sure you convincingly made the point you started out to make with this analysis.

Thanks for your thoughtful post.

ReplyDeleteI’m curious about your info on the 1.5F increase in temperatures.

ReplyDeleteUnadjusted temps show a slight cooling trend.

Eric - the fact that we are still learning is far from unfortunate.

ReplyDeleteNew study from B.C. fyi - Canada's scientists conclude that human-induced climate change had a strong impact on forest fires in British Columbia

ReplyDeleteThe study, led by research scientists from Environment and Climate Change Canada and the Pacific Climate Impacts Consortium at the University of Victoria, used climate simulations to compare two scenarios: one with realistic amounts of human influence on the climate and one with minimal human influence. Researchers determined that the extreme summer temperatures during the 2017 British Columbia forest fire season were made over twenty times more likely by human-induced climate change. Extreme high temperatures combined with dry conditions increase the likelihood of wildfire ignition and spread.