Today is the 77th anniversary of D-Day, the day when the allies landed hundreds of thousands of troops on the beaches of Normandy.

What is not well known is that weather forecasting played a crucial role in the victory of the Allies.

And there have been recent analyses by Anders Persson of the meteorological situation that provided new insights into the weather predictions that guided the decision to launch the invasion.

June 6, 1944

The landing on Normandy had several key environmental requirements. A full moon was required to provide sufficient illumination for gliders and parachute troops the prior evening. There could not be a low cloud base that would prevent close air support and accurate naval bombardment along the coast. Low tide conditions were needed so dangerous beach obstacles could be avoided. Furthermore, winds had to be light, so that waves and swell would be minimal.

June 4-7th would have the requisite lunar and tide conditions, with the next opportunity not until later in the month. And it was a matter of time before the Germans figured out where the real invasion would take place. There was strong pressure to move sooner than later.

Three forecast groups were represented in the overall meteorological team, two British (UK Meteorological Office and British Navy) and one American (headed by Dr. Irving Crick). The meteorological leader was the Royal Air Force's, James Stagg. The British meteorologists made use of traditional forecasting approaches that relied on the Norwegian Cyclone Model, with a typical evolution of cyclones and fronts (see below), while the American's used a controversial "analog" approach, where one searched for similar weather situations in the past.

Weather prediction was a primitive, subjective affair at that time. There were no numerical weather prediction models, little understanding of jet streams and upper-level weather features, and an acute lack of observations, particularly over the ocean.

The situation on June 4, 1944 was problematic (see sea level pressure analysis below). A fairly strong low center was approaching northern Scotland. The lines are isobars, lines of constant pressure, and where they are close together the winds would be too strong. Plus, a cold front was approaching (the line with the triangles on it). Not good.

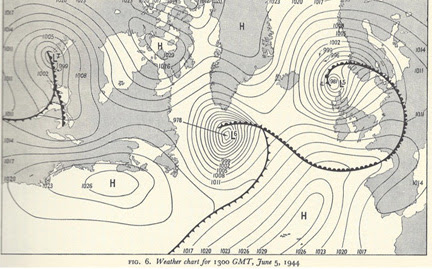

The weather map on June 5th indicated that the low had strengthened but had moved to the northeast (see below). An area of high pressure centered west of Spain was starting to extend northward into the region. Winds would still be significant but the situation might be improving.

The forecast team until Stagg predicted the low would continue to move northward, producing conditions just good enough for D-Day on June 6th. The actual weather map for June 6th (below) suggests that Stagg and associates made the right forecast for the wrong reason.

The storm did NOT move to the northeast as predicted but weakened rapidly as it slid to the southeast. And the pressure differences over the channel were large enough to create significant wave action, which caused extensive sea sickness, high water levels on the beaches, and lost equipment and deaths. Marginal, but just good enough for the landings on Normandy.

It has been thought that the German's had poor weather maps over the eastern Atlantic because they had few weather assets over the Atlantic (and none over North America). But as noted in the article by Ander Persson, it appears the Germans had decoded Allied weather communications and possessed relatively decent weather maps. They assumed that the marginal conditions on June 6th were not good enough for an invasion, resulting in a lack of readiness and the absence of General Erwin Rommel to visit his wife on her birthday.

Weather conditions were particularly important for the British and American militaries during the war because of their dependence on air superiority to overwhelm German tanks and other assets.

World War II represents the first war in which meteorologists played a critical role in guiding and supporting the American military. Today, the U.S. military invests substantial resources into weather prediction, including major groups in the U.S. Navy (e.g., Fleet Numerical Meteorology and Oceanography Center, Naval Research Labs) and the U.S. Air Force.

A critical forecast, for sure. Another was when the weather plane in advance of the Kokura atomic attack found cloudy skies over their primary target and went on to their secondary, Hiroshima. Walter Alavarez was on that plane.

ReplyDeleteThe secondary target for the August 9th, 1945, atomic attack was Nagasaki, not Hiroshima. That city had already been destroyed on August 6th, 1945.

DeleteThe decision to bypass Kokura for Nagasaki because of poor weather conditions over Kokura was made by Commander Frederick Ashworth, US Navy, the weaponeer.

While Major Sweeney, US Army Air Force, was in command of the aircraft carrying the bomb, Commander Ashworth as bomb weaponeer was in overall command of the mission.

It was Ashworth who decided to risk the safe return of the B-29's because of their low fuel situation and to attack Nagasaki instead.

Wasn't it Luis Alvarez the physicist on the plane? Don't think his son Walter was born yet.

DeleteAnother critical factor was Hitler being asleep, with strict orders not to be awakened. Additionally, he dithered in releasing the Panzers to go to the front when it was obvious where the real invasion was occurring. I grew up with parades every Memorial Day, most cities and towns don't hold them anymore - a sad commentary.

ReplyDeleteGood thing that the weather cooperated...or my wife might not have been born!!!

ReplyDelete