---John Steinbeck, East of Eden

___________________________________________________________

After the heavy rains of the past few days over central and northern California, a number of media outlets are talking about California suffering from "Weather Whiplash", since the record precipitation this autumn follows a year of drier than normal conditions.

And several media outlets are going much further, claiming the the "whiplash" is the result of climate change and is worsening over time (see below). Such articles quote from scientists whose research suggested increasing whiplash based on their examination of climate model projections.Well, what is the truth?

Global warming has been significant for several decades so we should see evidence of increasing "whiplash" if climate change is a major forcing mechanism. Strangely, none of the handful of studies in the scientific literature on whiplash has looked at the observational record. Just the climate models.

But in this blog, the analysis will be done!

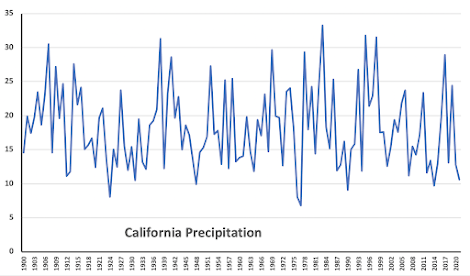

Let's examine the NOAA/NWS climate division data for California, and specifically, the precipitation for California's wet season of November through March from 1900 through 2021 (see below).

One is struck by several things.

There is really not much trend in California's winter precipitation.

And there is a lot of up and down variability---yes, weather whiplash. But there does not seem to be any long-term trend for more or less precipitation whiplash.

To illustrate this point, let's plot the yearly whiplash...a WHIPLASH INDEX.. by simply taking the difference between each year's and the previous year's winter precipitation for California. Since we don't care which way the whiplash goes (wet to dry or dry to wet), I will plot the absolute value of the difference. I also plotted (red dots), a 10-year moving average to smooth out the variation over time (see below).

Really very little long-term trend in California precipitation whiplash, with the worst of it from roughly 1975 to 1997.

Will whiplash get worse in the future?

I am involved in regional climate simulations, using an ensemble of high-resolution projections driven by an ensemble of many global climate models. This is the gold standard for such work. We ran these simulations using the highly aggressive RCP 8.5 scenario for increasing greenhouse gases, which is certainly not realistic since it assumes that mankind keeps on burning increasing amounts of coal, among other things.

Below are the results for Red Bluff in northern California (winter precipitation) through 2100, with the green lines being the average of the many forecasts. During the end of the century, there is perhaps some suggestion of occasionally larger whiplash, but also extended periods of less whiplash. But again, the amount of CO2 emissions is undoubtedly too large.

I think the jury is still out on whether California whiplash will increase significantly during the second half of this century. And the research studies that have suggested big increases during this century also predicted major whiplash increases during the past two decades. These have not verified with observations.

"Whiplash" isn't just about how much rain they get though, it's about extremes between drought and heavy rainfall, and you're only telling half the story here.

ReplyDeleteIt does look like rainfall in California has been relatively consistent over the last 100 years, but at the same time if you look at something like the Palmer Drought Severity Index, you can see that there are many more severe drought days in the last 20 years. Coupled with a consistent amount of rainfall and you get...more whiplash.

You can generate your own time-series data here: https://wrcc.dri.edu/wwdt/time or look at Graph 2 here: https://www.cteonline.org/cabinet/file/872591a5-20f4-4d7c-8770-72decb417528/Lesson2HistoryCaliforniaDrought.pdf

the warming is relatively steady, so it would contribute to drying in BOTH wet and dry years. Thus, it does not add to whiplash. Keep in mind that all summers in CA are dry...cliff

DeleteI don't understand what you're saying here.

DeleteThis seems pretty straightforward: if rain stays steady, but there's more drought, then it's going to feel more whiplashy, because it is more whiplashy.

You can't mix different things. If whiplash is dealing with precipitation there is no increase in whiplash. Drought is a very ill-defined term. What quantitatively do you want to define as your whiplash index? Need something objective that we can test!

DeleteWhiplash isn't JUST dealing with precipitation though, it's about how often you go from extreme to extreme.

DeleteIf you want a concrete "whiplash index", I'd probably want to represent how much the Palmer Drought Severity Index and rainfall are diverging (something like the absolute value of a scaled subtraction?). Basically, something where if they were seeing tons of droughts and also tons of rainfall -- very whiplashy! -- the number would go up. And if they move in tandem (more rain with less drought, or less rain with more drought -- not very whiplashy!) the value wouldn't change.

Oh the Alarmist never ending crisis crowd sure isn’t going to like your sober analysis Cliff. Where’s the panic and justification for more authoritarianism which they crave? They want to ride the panic wave from COVID right in to Climategeddon. You are “raining” on their “charade.”

ReplyDeleteThat's a considerable stretch, Jeff.

DeleteThe current leadership in DC has made this strategy clear...it's called "stray voltage," and their aim is to keep the population in a continuing panic mode , basically forever.

DeleteWhat about the data showing how the increased temperature, which is reflected in the data, contributes to more drying regardless of change in overall precipitation? Isn't the issue also not that there is a variation from year to year, but rather an increase in extremeness within the precip year? i.e. long dry periods followed by extreme flooding WITHIN the same year?

ReplyDeleteDaniel Swain talks about this on his social media page

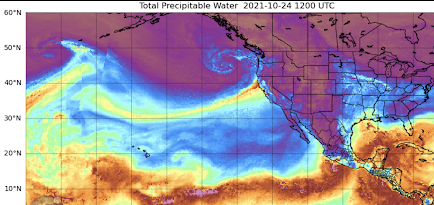

https://twitter.com/Weather_West/status/1448393548810702848

You need something objective and specific. Yes, temperature is going up. Precipitation is not changing much.

DeleteWhat is sorely lacking in many media discussions and, in the discussions a certain climate scientist you bring up here, Unknown is a thorough analysis of historic variability, and furthermore the limitations of the climate models. Cliff on the other hand, has risked his career, and has been defamed by peers and media because he holds science to such a high standard, even when it means calling out some of the poor science in the political, global warming narrative. As a nurse pursuing advanced practice, science is a requirement for best practice for me. Cliff is a hero to the broader scientific community.

DeleteThe dude with tenure at a major research university has risked his career? I'm not sure about that. Cliff is a mainstream climate scientist, publishes in regular peer-reviewed journals, receives major grant funding, etc. From my vantage point his is not a scientific martyr, just a researcher who is occasionally in disagreement with some in his field (e.g., Daniel Swain, I guess), which is a totally normal and healthy part of science.

DeleteUnknown...the warming is relatively steady, so it would contribute to drying in BOTH wet and dry years. Thus, it does not add to whiplash. Keep in mind that all summers in CA are dry...cliff

ReplyDeleteThe plot of model results at Red Bluff with the observed as black dots well off the modeled climate suggests that those models need some work or that the widely variable nature of precipitation in California is going to be really difficult to model.

ReplyDeleteYou bet. There is on offset...which could be a resolution issue for the specific station.

DeleteInteresting…looks like there might be a correlation between your whiplash index and the PDO

ReplyDeleteIn Sacramento no measurably rainfall for over 200 days, and then breaking the all-time record 24hr rainfall in a day in October is certainly unprecedented variability.

ReplyDeleteWhether or not it is considered 'whiplash', or is part of longer trend are issues that will only be settled as the future unfolds.

But unprecedented is a solid conclusion or headline folks.

Mr Issac, you bring up a valid point, however your sample size is tiny—-the dataset only contributes to a relative 100-200 years of record keeping. In comparison to earth time this tiny. Likely a modern day value of a shiba inu coin. What the climate science community in my sourthernmost west coast state needs to call out, like This blogpost does so well is the variability of this state and how actually normal that is,

DeleteIt would be interesting to see an analysis of this whiplash index with other known weather cycles like ENSO or PDO. Seems like those kinds of ocean temp variations would be the main contributors to any kind of variation in the wet vs dry periods in CA.

ReplyDeleteIt would be interesting to look at that data for some specific locations in northern and southern CA. The geographic concept of 'California' is relatively meaningless in terms of weather and climate. The state includes the Redwoods and Death Valley, so of course precipitation variability over such a large area shows little trend.

ReplyDeleteJoan Didion recounted many of the drought years in her memoir about growing up in LA - she wrote of a series of wildfires that came close to burning down the entire city...in the 1930's. Richard Henry Dana wrote about a catastrophic fire in Santa Barbara in the 1830's in his book "Two Years Before the Mast." It bears repeating that extreme drought and wildfire has been a part of CA since long before humans came along.

ReplyDeleteSlightly off topic, but I found this (https://cepsym.org/Sympro1996/Goodridge.pdf) to be an interesting read. Notably, while yes this latest AR was significant (no doubt), the short duration of it made precipitation totals fall far short of many, many other events in recorded/observed California weather history. Note also that the attached only goes up to 1996.

ReplyDeleteCalifornia has definitely been seeing a LOT of strange weather patterns in the last few years. At least these anomalies are above the ground and not below them (earthquakes).

ReplyDeleteI believe it's just even more signs of global warming which will undoubtedly be ignored by the crowd of people who can actually do something about it.

I was searching for PSN cards and somehow landed on this blogspot post which I thought was weird but since I'm from California I figured I would leave my 2 cents.

" by the crowd of people who can actually do something about it "

DeleteThat's good for laugh.

Instead of whining about others who supposedly should be making sacrifices, how about you setting an example and making some yourself? Give up your car, your home, any petroleum based products...and that's just for starters

DeleteOn your previous post I asked something kinda similar to this, got my answer!

ReplyDeleteAlso you should do a post about the blob not affecting us anymore! I had a big thing on another weather blog (Mark nelson, you probably have heard of him) Also congrats on 65 Million views

I'll copy and paste what I've said before

There is some big news for our winter….

https://coralreefwatch.noaa.gov/data/5km/v3.1/current/animation/gif/ssta_animation_30day_large.gif

We are no longer affected by the blob for the first time in years, over the last 4 days, the cool gulf of Alaska has dramatically gone south, so much so we aren’t affected by the blob!

And for our la nina, I’ve done a lot of research the last couple of days (ocean temp archives are surprisingly hard to find!) Over our last 5 extreme la nina’s, None of them were this cool in October! To make this clear, I do not think that guarantees a extreme La Ninã, but it’s looking really good!

Would like to hear other people's thoughts of this ESPECIALLY Cliffs!

-Hank from Salem

Isn't it true that while the average precip may not change much the frequency of extreme events is projected to increase using the same model: "Climate model simulations under the RCP8.5 project that in the future, the frequency of what is currently a 50-year event could double in both Southern California (i.e., San Diego, and Santa Barbara) and Northern California (i.e., San Jose and San Francisco). This means

ReplyDeletethat highly populated areas across California may experience extreme precipitation that is more intense and twice as frequent, relative to historical records, despite the expectation that, on average, annual mean precipitation will not change substantially. " PROJECTED CHANGES IN CALIFORNIA’S PRECIPITATION

INTENSITY-DURATION-FREQUENCY CURVES. Amir AghaKouchak1, Elisa Ragno1, Charlotte Love1, Hamed Moftakhari UC Irvine CCCA4-CEC-2018-005

1 University of California, Irvine

I think the weather whiplash in California is within the annual cycle rather than between them. In other words, perhaps it's because the summers are dryer and the winters wetter - more extreme on a month by month basis, but not necessarily year over year.

ReplyDeleteHigher overall temperatures may also be affecting the effect of the precipitation, even if the actual amount has not changed. Higher temperatures could result in more water loss through evaporation and transpiration, leading to dryer topsoil and vegetation, which in turn might lead to more runoff, erosion, vegetation loss, and flooding. If that's the case then you might be able to look at the effects rather than the amount of precipitation - surface moisture levels in places that are not irrigated, or changes in lake and river levels month over month. Water management would affect those levels as well, but sudden swings should still be primarily affected by the combination of precipitation intensity and the properties of the watershed.

Increased development in the watershed would also lead to more runoff, though... so it's probably not as simple of an indicator as raw precipitation - too many extra variables. Maybe if you could find a California watershed untouched by development for the last 100 years... but that seems unlikely.

I think the whiplash is not so much going from a wet to a dry year or even a change in overall annual precipitation over time, but the extremes that are being experienced in relation to both precipitation and temperature. At a farm near Davis where I used to work (1996-2001), they wrote earlier today about it: "By Sunday morning at 8 a.m., we had already gotten more rain in a single day than we have ever had in one day in October — 3″. And by the next morning, we had gotten more rain than we have ever had in October before: 7.25″. And the historic statistics don’t end there. In a single day, we got more rain than we did in all of the 2020-2021 winter." https://terrafirmafarm.com/2021/10/27/famine-to-feast/

ReplyDeleteGreat quote to start the story. Headlines benefit from and seem to promote weather amnesia.

ReplyDeleteI highly recommend this book for folks who want to understand the science and the history of drought and flood in California.

ReplyDeleteThe West Without Water

What Past Floods, Droughts, and Other Climatic Clues Tell Us About Tomorrow

by Ingram, B. Lynn

Book - 2013

Would be interesting to see a statistical graph for CA water consumption over the same graph in Cliff's whiplash post.

ReplyDeleteIn the final plot, does the high quantity of observed data being below the projected green line indicate difficulty in prediction?

ReplyDeleteIs there then the potential that we are under estimating the impacts of climate change on total precipitation in California? This would then indicate a higher probability for decreased annual rainfall meaning the 'whiplash' (increased annual rainfall for a short period of time) occurrence would seem more drastic despite having occurred less frequently.

You are still failing to show the intensity of major precipitation events over the long term period for a winter. That was the point of "whiplash". Intense events compared to moderate events over a period of time--the intense events are becoming more frequent. This is something that the Seattle Times called you out on. If the intense events are the same and are as frequent, then please show the data. Thank you.

ReplyDeletethe "whiplash" being discussed is seasonal, not event by event. In any case, the most intense events are not becoming more intense. Do you have any evidence of that? If so, please provide the reference...cliff

DeleteCalifornia is huge. Is it meaningful to treat is as one locality for this analysis? If so, how was the rainfall total for the entire state calculated, and how accurate were these calculations for the 100+ year old years?

ReplyDeleteIf anthropogenic warming is real (and I believe it is), then why is it hard to accept that ALL weather events are affected by it to a some extent? Certainly most events would only be affected to a minute, undetectable degree. But we are talking about adding energy to an interconnected, global system, and when we do that it is going to change things, whether we know how to measure them or not.

ReplyDeleteWeather West blog accuses you of 'Not discussing Climate Change' guess they were wrong. I bet they just want to spout it out to promote their CCP agenda.

ReplyDelete