My podcast today will both provide the weekend weather forecast and talk about the history of wildfires in the Pacific Northwest.

Wildfires and associated smoke are a major concern in the region, and some media, politicians, and others have suggested that wildfires and wildfire smoke are not normal and are a potent sign of a changing climate.

They are not correct. Wildfires and their smoke are a natural part of the Northwest ecosystem.

What was not normal was the period of suppressed fire during the later portion of the 20th century.

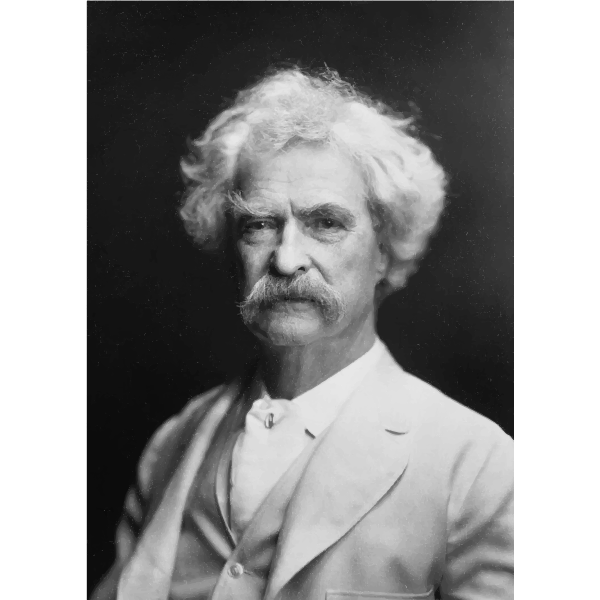

A good illustration is the visit of Mark Twain in August 1895, a summer in which the U.S. Weather Bureau noted "the sun was almost entirely obscured by excessive smoke from wildfires." Twain was invited to speak in Olympia, where the chairman of the reception committee apologized for "smoke so dense that you cannot see our mountains and our forests, which are now on fire". Twain retorted

“As for the smoke, I do not so much mind, I am accustomed to that. I am a perpetual smoker myself.”

A Region of Fire

There is a great deal of research, some of it based on charcoal deposits underground and others from tree-ring cores, that fire is a regular feature of our region for millennia.

This work has found that westside forests typically burn every few hundred years and eastside forests every decade or so. Wildfire is an essential part of Northwest ecology, something well-known to Native Americans, who regularly started fires to improve the productivity of the landscape.

When European explorers and settlers reached the region hundreds of years ago, they frequently commented about summer wildfires.

For example, during August 1788, European explorers sailing up the Northwest coast noted massive smoke from great fires (Indians, Fire and the Land in the Pacific Northwest, edited by Robert Boyd, 1999)

The non-Native American

settlers that entered the Northwest during the early to mid-1800s noted frequent

fires and smoky summers. For

example, in September 1844, a wildfire descended the hills and nearly reached Fort

Vancouver, north of present-day Portland.

A year later, the Great Fire of

1845 burned through the northern half of Lincoln County and the southern

half of Tillamook County, Oregon, destroying much of the old-growth timber of

the area (1.5 million acres). In 1853, the Yaquina fire engulfed

450,000 acres, followed by the Silverton Fire of 1865 (covering million acres)

and the 1868 Coos Fire (300,000 acres), all on the western side of Oregon.

September 1868 was a very bad year for fires and smoke. Residents of Olympia, Portland, and Oregon City were forced to use lamps in the daytime to carry on normal activities because the smoke was so dense and dark.

I could provide dozens of reports in newspapers and journals documenting the typical smoky summers of the Pacific Northwest, on both sides of the Cascades.

This smoky regime continued into the early 20th century, until the great wildfire of 1910, the Big Burn, seared a large area of eastern WA, northern Idaho, and western Montana. An event that killed 87 people. That fire led to the invigoration of the U.S. Forest Service and the goal of actively suppressing fires.

But it wasn't until the 1940s, that the technological capability to massively and effectively suppress fires was in place and the result was a collapse of fire area in the western U.S. The era of Smokey Bear had begun.

A plot of Oregon wildfires below tells the story. A huge decline in wildfire area around 1940. This collapse in fires was not climate change, but human intervention.

During the past few decades (the 1970s to today) more fire has returned to the Northwest landscape but NOTHING like the wildfires before human intervention.

- Some of the wildfire increase is due to the policy of allowing some fires to burn (based on understanding the important ecological role of fire).

- Some of it is due to increased human ignition of fires (from our electrical infrastructure, arson, and accidental fire starts).

- Some of it is due to the massive invasion of foreign flammable invasive grasses into our region.

- Much of it is due to the massive changes in our forests, with fire suppression and poor forest practices, leading to unnaturally dense timber stands littered with past logging debris that burn so intensely and catastrophically that we cannot control them.

- Some of it might be associated with the relatively minor global warming (1-2F) that has influenced our region.

I believe the evidence is that the climate change component is a small player today in increasing wildfire frequency, with the other factors being more important.

In any case...and the important message in this blog... is that wildfire is a natural element of Northwest ecology and meteorology and that the 50-year period of suppressed wildfire and smoke are anomalies from the natural state of the region.

To listen to my podcast, use the link below or access it through your favorite podcast service.

Some major podcast servers:

Like the podcast? Support on Patreon

A good way to convey and understand temperature changes so far is with the NASA climate time machine. It is curious how Asia and Europe seem to be heating faster than North America: https://climate.nasa.gov/interactives/climate-time-machine

ReplyDeleteThat NASA visualizer makes comparisons to "average temperature" but has no explanation what is meant by average temperature. This makes me suspect its veracity.

DeleteLate summer fires and smoke may be natural, but it doesn't mean that we have to like it! In fact most of us don't. Talk about in inconvenient truth, as Al Gore would say.

ReplyDeleteI guess we have to decide between living in the (mostly) sunny (except when burning) West, or the humid east with the mosquitoes, deer-flies, and ticks. Or the Mojave Desert, which is so dry there is nothing to burn.

Thanks for this overdue perspective, Cliff. What's "normal" always begs the question of "for when and where?" Not many thousands of years ago, Seattle, Chicago, and New York locations were all under huge ice sheets and the sea levels were a lot lower than they are now. I suspect there were not many wild fires in this area then!

ReplyDeleteFire suppression is killing our forests and eliminating browse for animals. I am sitting on a ridge in Eastern Oregon right now that 30yrs ago was mature Lodgepole Pine with grasses spread all over the forest floor. Now Silver Firs are choking out the environment and there is little feed left on the floor. Firs are native to the area but they were kept in check by regular fires. Without management or regular burns we have a lot of forests that are going to become wildlife dead zones in the next 50 yrs.

ReplyDeletegreat review of the forest fire history of the PNW and impact of human interventions

ReplyDeleteYour comment about "mismanagement of forests" is incorrect. The Indians managed the western forests for over 10,000 years for THEIR needs. Basically, to manage the wildlands for camas and other native species for food and other products. The landscape evolved to meet the needs of the Indians.

ReplyDeleteWhen Europeans showed up in the American west, we started to manage the forests for industrial development and putting up McMansions in Bellevue. That meant denser forests.

Then in 1986, we decided to quit managing our forests for fiber production and instead focused on "protecting" them. Unfortunately, that just resulted in a "epidemic of trees". That burned and will continue burning for another 30 years until we convert our National Forests to National Brush Fields. It will be a significant ecological change in the west.

Not mismanagement of our forests. We made a deliberate decision and these are the consequences. It isn't a right or wrong decision.

My only regret is that we are literally burning the soils, which means for centuries into the future our current forests, will be brushfields.

Indians? We Europeans? Semantics aside, the native American interaction with the land turned out to be ecologically superior, as one would expect since they used natural processes and were dependent on the land for their very survival, quite unlike Westernized practices on the landscape.

DeleteThe "Big Burn" is a hard read, but fascinating:

ReplyDeletehttps://www.timothyeganbooks.com/the-big-burn

Lets remember that human intervention also caused many of the fires pre-1900, in the form of fires set by indigenous and immigrant human beings. And lightening of course.

ReplyDeleteThe Big Burn in Montana in 1910 is covered in Tim Egan's outstanding book (Big Burn), one of his best. It also covers Roosevelt, Pinchot interesting developments in the Department of the Interior.

ReplyDeleteYou list five factors that you believe have contributed to the recent increase in fire activity in the West and you seem to indicate that past poor forest management is the main contributor. I doubt that you could prove that past poor forest management is a greater contributor than say climate change, which is bringing more severe fire weather seasons, or some of the other factors you listed. The issue with blaming past forest management (i.e., promptly attacking and extinguishing fires) is that this tactic was favored by the majority of the people, who did not want to see our forests burned up and have to endure smokey skies every summer. I would say this tactic is still favored by the majority of people, especially now that there are so many people living and recreating in our forests. The decision of whether to attack fires or not has been an issue certainly around North Central Washington is recent years as forest managers try to decide which ones to attack and which to let burn.

ReplyDeleteActually it does seem that it can be proven by the majority of peer reviewed studies, as mentioned on the podcast

DeleteCliff's graph of wildfire statistics shows the sharp drop in fires after about 1940 which he attributes to improved fire control methods. I agree this was a factor but I can also show you that fire season weather severity also declined sharply from about 1940 through about the mid 1960s in eastern Washington, rose again through the 1970s, then after a short period of decline in the early 1980s, has been more severe in recent years. The fire season weather severity (warm temperatures, low humidity, scant rainfall) showed a number of high severity years in the 1920s through the 1930s prior to 1940. While I believe past forest practices were a factor I still think it would be difficult to prove that they were a bigger factor than changes in fire weather severity from year to year.

DeleteMany of the really bad fires during the last century were caused by poor logging practices that not only started a lot of fires but left large areas of slash debris that acted as an accelerate to get western slope fires burning more severely than would normally occur.

ReplyDeleteFires in Alaska were not suppressed except for a small percentage near urban areas (Sci. Am. Oct 2021). But Alaska has been hit with some of the worst fires of this decade including this year. Ditto for Siberia and Northern British Columbia during this decade. So I'm not sure suppression can be considered the major cause of increased fires worldwide, certainly contributory in the lower 48 but maybe not the root problem.

I was going to make a similar point. The focus of this post is a bit too local, even granting the PNW emphasis of the blog. Mismanagement certainly plays some role in the recent uptick in fire in the US west, but doesn't account for similar trends in global forest that weren't subject to out by 10am policies.

DeleteI agree. In addition to wildfires in areas where fire suppression never happened, the PNW has experienced many weather extremes in recent years that seem like they would obviously contribute to wildfire risk. Record high temps, record long periods without rain, and we just had the driest summer on record. Cliff would probably say that none of that was caused by climate change, climate change can only cause 1-2 F warming, but I don't think most people are buying that anymore. (If we have enough hot, dry summers in a row, doesn't it become climate change by definition?)

DeleteIn Roughing It, Twain claims that he and a friend started a massive forest fire on the bank of Lake Tahoe. So it appears he had little standing to complain about our forest fires, anyway.

ReplyDeleteJust as with global warming, it is very difficult, if not impossible to blame a particular event on past forest practices. Take the Bolt Fire, for example. Previous fire suppression could have played a part in its very rapid rise. I don't see it. To begin with, if west side fires happen every 100 years or so, then fire suppression on the west side has had a minor effect. The forests aren't that different. In contrast, they have radically changed east side forest. But the fire also has other issues that hopefully you (Cliff Mass) can shed some light on.

ReplyDeleteThe fire occurred as the result of unusually hot, dry and windy air coming from the east. How often does this occur (on average). It also appears that it was man made (not caused by lightning). How often would we get that strong east wind and lightning? If the answer is "very rarely" than fires like this one appear to be rare. We would instead get fires like the one in the Suiattle (which has grown slowly).

From a larger perspective, I wonder how many fires are naturally occurring, and how many were not. I can think of some very big ones started by power lines, fireworks, and whatever started the Bolt Fire. Fire is normal. But perhaps we are dealing with an unnatural set of fires -- fires that are especially big on a routine basis -- because of past forest practices and man-made fires.

Oh, and as mentioned earlier, there is also logging. Fire suppression creates an unnatural forest -- a type different than 1,000 years ago -- but so does logging.

Thanks Cliff for confirming what my grandmother who was born in 1901 and spent her whole life in Seattle told me. She said growing up as a child, many summers they couldn't see the mountains for the smoke. As a lifelong Democrat, environmental and progressive activist it completely escaped her as it does many others now that decades later there would be an ecological cost to interrupting the natural process of wildfire, or that the cost of mostly eliminating old growth timber wouldn't just be a reduction in owl populations.

ReplyDelete