There is been a lot of talk about the huge amount of snow and rain hitting California, where the drought of the previous few years is now clearly over.

But with the bulk of precipitation heading south of the Northwest during the past month or so, where does that leave the Pacific Northwest? How is our snowpack doing? Are our reservoirs filling? Are we in water trouble?

It is time to check this out, particularly as we are moving into the drier Northwest spring.

The bottom line: Washington State water storage is modestly below normal, with no serious water issues expected.

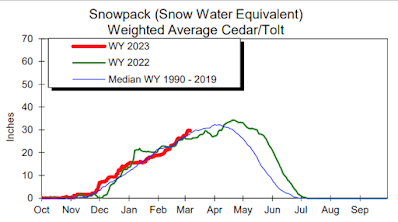

First, the snowpack. Oregon snowpack is well above normal and Washington State snowpack is generally near normal, although a bit below normal for the Yakima Basin and the North Cascades.

Next, let's turn to the Yakima River reservoir system, which is very important for agriculture over eastern Washington (see below). It is also below normal (roughly 85% of normal).

To get a broader view, below is the Water Supply Forecast for this summer from the NOAA River Forecast Center. Near normal (green) for western Washington and northwest Oregon, as well as southeast Washington and much of Idaho.

Now let me note that earlier this winter, my profession was calling for a cool/wet winter because of La Nina. We got the cool, but not the wet. We also thought California would be drier than normal.

Temperatures? Disappointedly no warm-up for the heat-starved residents of the Northwest (see the prediction for the next 10 days below)

The Pacific Northwest Weather Workshop is the region's premium weather gathering, and it is back as an in-person meeting on May 12-13th at NOAA's Sand Point facility in Seattle. This will be a hybrid meeting, so those of you who wish to attend remotely can do that as well.

At this workshop, we discuss the latest advances and studies regarding Northwest meteorology and climate (including British Columbia) and review the major weather events of the past year.

The upcoming meeting will include talks on advances in regional weather prediction technology, the Portland snow bust, the December ice storm, wildfire meteorology, the autumn smoke event, new initiatives in media weather, regional climate change, and much more.

We will also have a banquet at Ivar's Salmon House (in Seattle) on Friday evening, with an engaging speaker.

If you are interested in attending, you can get more information and register at the meeting website:

https://a.atmos.washington.edu/pnww/

And those interested in giving a talk, please send me a title and abstract by April 10.

.png)

I understand about the lakes and so on being at near normal levels but a large portion of the populace in WA is using wells either private or municipal wells. I know it takes time for the moisture to reach the aquifer. Just because the lakes are full we should still conserve as much as possible. Is the California drought REALLY over if the aquifers are going dry?

ReplyDeleteCalifornia and Western Washington are completely different situations. In Western Washington, aquifers do not run dry. They are replenished faster than we have ever pumped them out.

DeleteCalifornia is the opposite. Some of the most important aquifers are being pumped out much faster than they could ever be replenished, no matter how many atmospheric rivers California gets.

Agree with Jellybean here. We do not drain the swamps up this way and we often get enough rain to replenish the aquifers easily pretty much every year.

DeleteCalifornia is not in that position, especially the central and southern portions of the state as they can go YEARS between any significant rainfall to replenish their aquifers and they are using a lot of it for agriculture, let alone for all the water fountains found in urban areas and other wasteful water usage, so they are pumping out more water from those aquifers than they are able to replenish.

Part of the issue is Sacramento is in the more moist portion of the state, while the vast majority of the state's population is in SoCal where the water shortage is most acute and there is a disconnect between the two and a false sense of security with the Colorado river and even it is not adequate some years..

California may never have fully replenished aquifers because of the quirks of water rights in California agriculture which allow unlimited pumping

Deletehttps://medium.com/mother-jones/california-goes-nuts-daa3632e5c55

Immediate scarcity (actual or perceived) is also useful for certain political agendas which seek sociopolitical structural change, even if there’s an element of absurdity (water shortage in the desert).

“You never want a serious crisis to go to waste. And what I mean by that is an opportunity to do things that you think you could not do before… This is an opportunity, what used to be long-term problems, be they in the health care area, energy area, education area, fiscal area, tax area, regulatory reform area, things that we had postponed for too long, that were long-term, are now immediate and must be dealt with.”

https://610kona.com/2023-irrigation-forecast-good-for-tri-cities-columbia-basin/

ReplyDeleteBureau of Rec sez it's okay according to this for E Wa

I've been observing precip in the same location for almost 50 years, here near Mt. Baker. II have no idea where USDA is getting its precipitation data, but I know for certain that in the 163 days since the current rain year began, we've had 35.99" precip - that's .22 inches per day. The USDA SNOTEL (909) Wells Creek reports 94" snowpack today, while 4 miles from that SNOTEL (almost the same elevation) the snowpack is 162-172" -- 18" new snow was reported there this morning. I emptied 1.04" rain from my gage this morning, and I'm observing rain-snow mix right here at an elevation at this moment, as I type. All that said, I do wonder about the credibility of that map.

ReplyDeleteWell, if you have followed snow data for Mt. Baker for 50 years and live in its shadow in Glacier, you have to know that Mt. Baker is one of the snowiest places, if not the snowiest place, on the planet. The Mt. Baker ski area typically receives 600-700 of snow a year. In the lowlands of this corner of the state, precipitation has been on the low side for some time. Bellingham is about 4" below normal for 2023 and about 7" below normal for the current water year starting on October 1. The last really substantial rains were the 6 days of heavy rains that caused damaging floods in November 2021 when Bellingham received about 15" of precipitation, which is fairly close to half of an entire year's precipitation for us.

DeleteI'm less concerned about water resources and more concerned about whether we'll receive sufficient dry season precipitation (non-convective, preferably) to put a damper on the wildfires and attendant smoke. Additionally, as we saw last year, even if summer is reasonably wildfire/smoke-free (locally, obviously smoke from distant wildfires can still be a nuisance) if the fall rains are delayed then the likelihood of significant wildfires/smoke in the PNW increases continuously as nearly all understory vegetation is tinder-dry by that point if summer is largely rainless. Fingers crossed for relatively regular summer precip (sans lightning) and a normal start-time to fall!

ReplyDeleteSummer precipitation...or even fall precipitation... is not the key issue. The big issue is easterly flow. Strong easterly flow dries things out in hours... and rapidly sets the stage for fire. Like last year...

DeleteActually, an ignition source, as well as dry fuels are the keys. Easterly flow certainly results in low relative humidity and dew points which serve to dry fuels and can bring smoke from fires burning to the east (which might have been extinguished, attenuated, or not have started or grown in the first place with normal precipitation) but without a source of ignition there would be no wildfire. Consider that wildfire is not an issue in this area during a wet season with normal precipitation despite the fact that easterly flow occurs regularly. Is this because ignition sources disappear during the wet season?

Delete